In the face of unprecedented flows of migrants, including refugees and asylum-seekers, governments around the world have an obligation to protect their universal human rights, and an interest in collaborating with all stakeholders to do so.

However, not only have many governments shown an inability or unwillingness to fulfill their obligations, many increasingly place limitations on human rights defenders and civil society organisations that seek to fill protection gaps and defend migrants’ rights.

ISHR welcomes the High Commissioner’s draft Principles and Practical Guidance on Respecting the Human Rights of Migrants in Vulnerable Situations tabled at the 34th session of the Human Rights Council, in particular Principle 18 which calls on States to respect all human rights defenders and organisations that provide assistance to migrants. In a nutshell, Principle 18 states that the legitimate work of human rights defenders should not be criminalised by national laws and policies but be protected and supported. Where defenders face violence, discrimination, intimidation or reprisals, State and non-State actors should be held accountable. The principle calls upon States to publicly promote the work of those supporting migrants, and highlights the need to ensure specific protection to defenders who are migrants, work on migrant women’s rights or disclose information about the human rights of migrants.This is an important step toward recognising the increasing restrictions these groups face.

It also reinforces ISHR’s decision to include a special focus on defenders of migrant and refugee rights as part of its Strategic Framework 2017-2020.

Executive Director Phil Lynch emphasises: ‘For this strategy, it was important to respond to our times, prioritising support to those defenders who work to confront power, privilege, inequality and exclusion. Against the rising tide of intolerance and illiberalism, this means standing with defenders of migrant and refugee rights’.

Sarah M Brooks, who leads ISHR’s work in this area, believes there is real potential for collaboration among these groups to push back on challenges to basic freedoms of association, assembly and expression. Innovative responses from the UN, she says, might help to address the trend.

‘The UN Human Rights Council and its mechanisms struggle to have concrete impacts on State policies on migrants. The practical guidance provided by the High Commissioner could have potential, because the failures of European and other governments to protect migrants, or active efforts worse push them back, are only half the story. Civil society organisations and defenders trying to support migrants are squeezed between an increased need for their work on the one hand, and an increase in restrictive laws and violent anti-immigrant discourse on the other’.

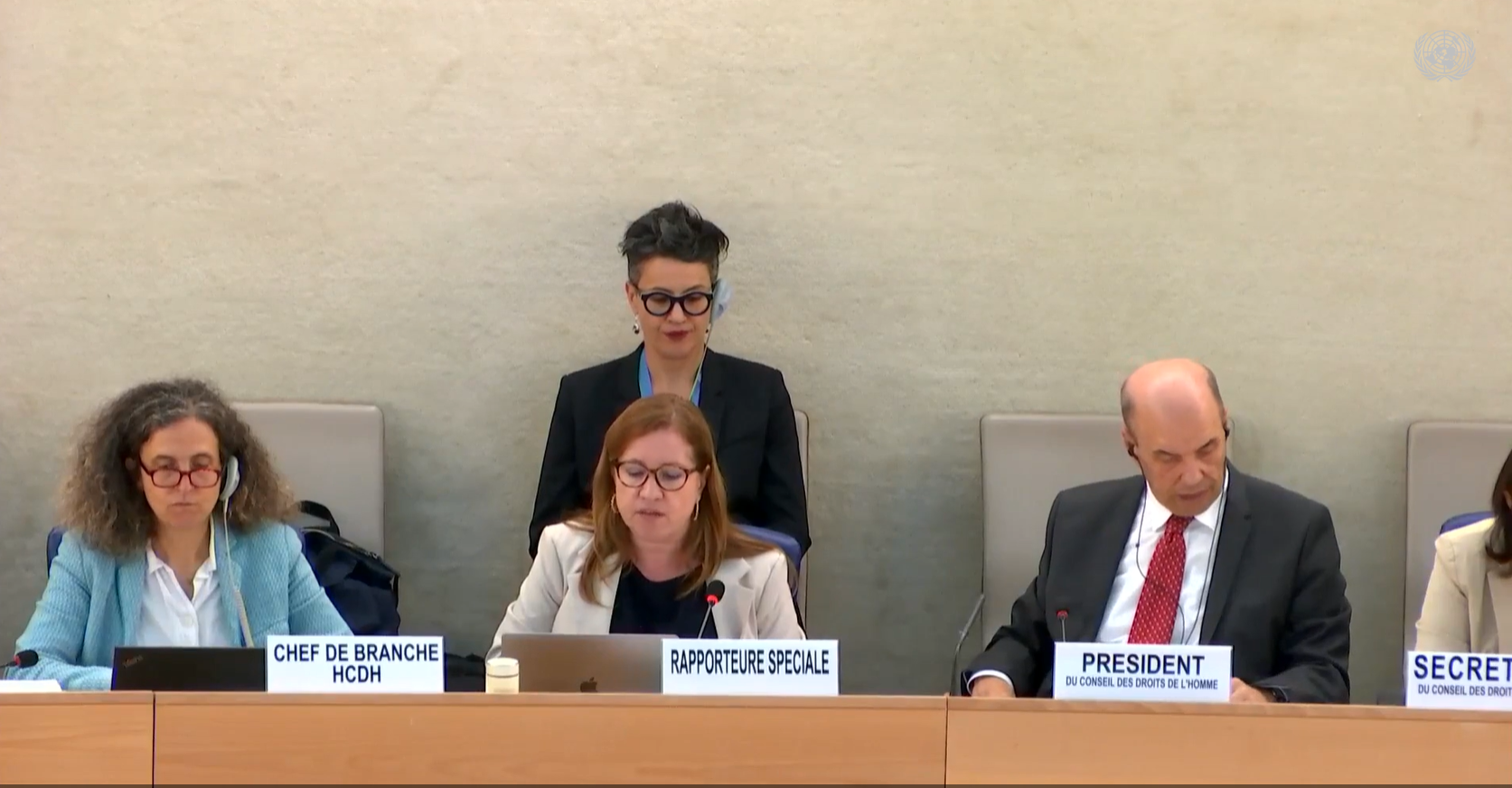

The Council’s Enhanced Dialogue on Migrants was another opportunity to hear from high-level UN officials and delegations about their efforts to protect the human rights of migrants; the sole civil society panelist, Monami Maulik, clearly argued the importance of civil society – and in particular, migrant-led organisations – being at the heart of planning and monitoring global efforts in the months ahead. The German delegation in their intervention noted the crucial role of human rights defenders to protect vulnerable migrants; Belgium emphasised the need for a safe and enabling environment for organisations providing assistance to migrants.

In some cases, barriers to supporting migrants’ rights are practical. For example, OHCHR has reported that human rights lawyers and civil society groups were denied access to their clients during the dismantling of the ‘Jungle’, a migrant settlement in Calais, France. Following his 2016 country mission to Australia, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders Michel Forst expressed concern at ‘vilification’, ‘stigmatisation’ and ‘retaliation’ against refugee rights defenders. ‘Lawyers and human rights advocates who assist refugees and asylum seekers in immigration detention in Australia face many barriers,’ he said.

ISHR’s statement to the UN Human Rights Council today highlighted restrictions on access to facilities housing unaccompanied migrant children in Serbia, and concerns by civil society groups in the country – including the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights – that these limitations, combined with legislation that creates a chilled environment overall for civil society, will have a negative impact on their operations and thus, on the migrants they seek to serve.

In other cases, some governments at national and local level are adopting legislation that criminalises assistance to migrants, or that places excessive restriction on public assembly and association and freedom of expression. In their day to day work, defenders of migrants’ rights face serious barriers. Special Rapporteur Forst highlighted this in statements reflecting on three of his last four country missions.

- In Australia, for example, the Border Force Act imposes secrecy provisions and ‘gagging’ clauses, restricting organisations working with migrants in detention centres from conducting advocacy and effectively forcing them to choose between providing services to refugees and speaking out when they witness abuse.

- During his visit to Hungary, activists raised concerns about government failures to protect migrants and defenders from far-right and extremist threats, and the use of excessive force against migrants during a demonstration, and journalists seeking to monitor that demonstration.

- In Mexico, the efforts of organisations and defenders to provide assistance to migrants in transit are under threat from criminal actors who extort, rape and kill, often with full impunity.

‘Challenging immigration practices that undermine human rights is a tough job,’ says Ms Brooks. ‘Just a few days ago, we heard about the serious threats faced by migrant rights defenders in the U.S., both criminalisation and stigmatisation, in the aftermath of the now-revised, but no less repulsive, Trump administration travel ban.’

‘The international community needs to be vigilant in ensuring that these defenders and groups, now more than ever, have the space to operate freely and without restriction and that their important contributions are recognised’.

For more information, contact Sarah at s.brooks[at]ishr.ch. You can follow her on Twitter @sarahmcneer.

More information on the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights can be accessed at http://www.bgcentar.org.rs/bgcentar/eng-lat/