By Deborah Brown, Senior Project Coordinator, and Jac Sm Kee, Women’s Rights Programme Manager, Association for Progressive Communications

In recent years, revelations of mass governmental surveillance have propelled the right to privacy into the public eye and discourse. However, equal attention needs to be given to surveillance practices by individuals against each other, as well as by the private sector and non-state actors. Mass surveillance is a grievous human rights violation, and public outrage is well deserved. But threats that at-risk users and marginalised groups experience are equally important. Human rights defenders and women human rights defenders (WHRDs), sexual rights activists, political opposition, religious and ethnic minorities, and independent journalists, in particular, are regularly subjected to surveillance and have their privacy rights persistently violated.

Importance of privacy online to women and women human rights defenders

Privacy helps to establish boundaries that limit who has access to our bodies, gives space to express ourselves, experiment without judgment, and think freely without discrimination. To put it simply, privacy allows us to imagine what we could be, and a world that is better than this one. It is also an important right in the exercise of autonomy and self-determination. This is particularly true for women and WHRDs, who rely on privacy online to assert their rights in the face of significant power imbalances, face online aggression, and to gain access to critical information, including those related to health and safety.

The Association for Progressive Communications’ (APC) work with WHRDs and survivors of harassment, in particular in the online environment, has demonstrated how important privacy online is to physical integrity offline. In particular, women are targeted because of the existing discrimination they face. Blackmail, extortion, persistent harassment and humiliation are all tactics used to silence women and WHRDs. Exposure of personal information such as name and geographical location (‘doxing’) poses an immediate offline risk to physical safety and employment to women in particular, and human rights defenders generally.

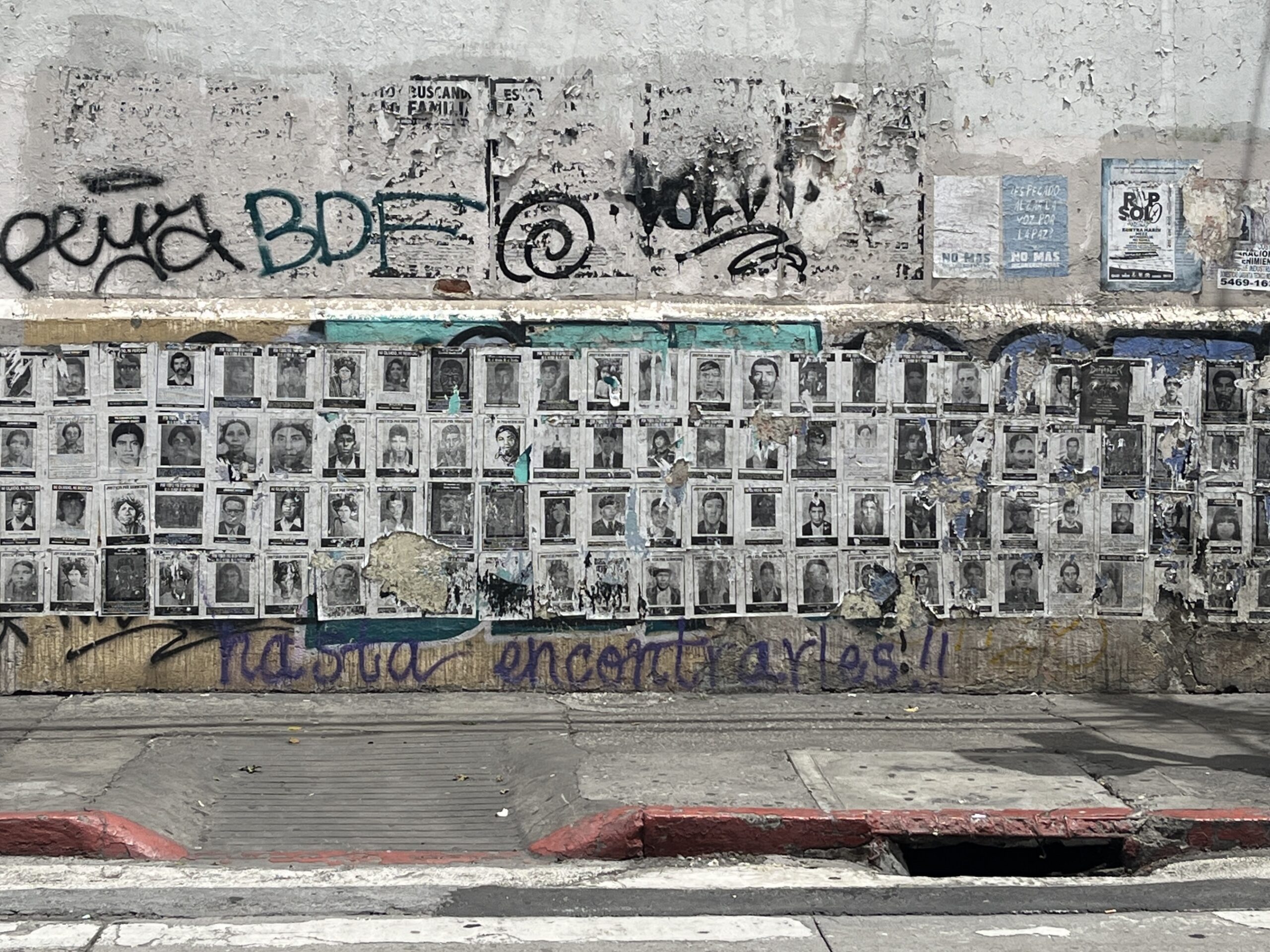

APC’s research conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Kenya, Mexico, Pakistan and the Philippines[1] has found that online anonymity, for example, can be a powerful tool for combating online harassment and technology-related violence against women. In particular, our research substantiated that online anonymity enables the targets of hate speech and violence online to engage with their aggressors and encourages counter-speech from broader communities. Since legal remedies often fail to recognise tech-related VAW, or incidents are not taken seriously by police, courts and other administrative systems, survivors use technology to face and monitor their aggressors, and rely on online anonymity in order to do so securely. As a result, WHRDs are learning to privatise their online presence in order to campaign without fear for themselves and their loved ones.

To give just one example, Antonia and other employees of the Colombian feminist organisation Mujeres Insumisas have faced constant and increasing threats admonishing them to stop working for women’s rights – some identified as being authored by paramilitary groups. As a result, the organisation designed and implemented self-protection privacy measures, including recommendations for database handling, movement to and from the office, managing location information for the team, and maintaining confidentiality on social networks.[2]

It is important to note that restrictions in legislation and regulation that are put in place for the expressed purpose of preventing online harassment often harm underprivileged groups while not effectively limiting their use by criminals who often have better access and training on using such tools. In states that crackdown on civil society, activists and minorities these regulations often take the form of disproportionate measures and are used as tools to punish or limit civil participation, circumvent due process, and frequently put the privacy of the majority at risk, through data retention for example.

Expectation of the new Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy

We welcome the Human Rights Council’s establishment of a new special procedure on the right to privacy as a necessary step to fill a significant gap in the conceptual and practical understanding of the right to privacy. We encourage the new special rapporteur to address the specific challenges that WHRDs and other at-risk communities face with respect to privacy, in particular the specific threats that individuals and communities face as a result of surveillance and the effective remedies to individuals whose rights to privacy have been violated. It is important for the new special rapporteur to integrate a gender perspective throughout the work of the mandate, and to reaffirm commitments to non-discrimination as a crosscutting principle in international human rights law. The new special rapporteur should look to UNGA resolution on Protecting Women Human Rights Defenders (resolution 68/181) for guidance in this respect.[3]