In 2014, Yu Wensheng represented the Chinese supporters of the Occupy Central Movement in Hong Kong. In 2016, he represented human rights lawyers, including Wang Quanzhang, who were targeted in mass arrests of civil rights lawyers. Between late 2017 and 2018, he publicly called for constitutional reform.

Yu’s efforts to improve the human rights situation and the legal system in China have, on the one hand, landed him in prison. On the other hand, it has earned him international recognition: in November 2018, he was awarded with the Franco-German Prize for Human Rights and Rule of Law, jointly granted by the French and German governments. In February 2021, he won the Martin Ennals Award for his work defending human rights in China.

Defending the supporters of Occupy Central Movement

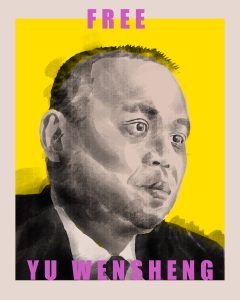

Despite looking older than his actual age – probably due to years of defending human rights, repeated detentions and surveillance -, Yu Wensheng is a man with sharp sense and clear words.

Born in 1967, Yu passed his bar examination in 1999. He used to practice commercial litigation, always “following the rules” within the system. In his words, he was “unwilling to confront the system, trying to avoid direct conflicts” with the authorities. He often said he felt “forced” to defend civil rights when the authorities acted unlawfully.

On 28 September 2014, the Occupy Central Movement, a campaign by Hongkongers calling for universal suffrage, sprang into action in Hong Kong. This evolved into the famous 79-Day Umbrella Movement. After hearing the news, civil rights activists in Beijing began to meet up and raised placards and posted photos online with messages in support of the Hong Kong protesters.

Starting on 30 September, these activists were detained one by one and interrogated intensively. Han Ying, a citizen, recalled that she was interrogated and deprived of sleep for nine days straight. She kept being asked, “why are you supporting Hong Kong? Who has funded you? Who is behind this?”

Universal suffrage is indeed a universal value.

But because of this, more than 100 Chinese citizens were arrested.

In response, Yu Wensheng and other human rights lawyers rushed to police stations to help. Chinese law stipulates that a lawyer has the right to meet their client after a 48-hour-detention, but Yu Wensheng was denied this right. The police told him to return home and wait for news, but he refused and insisted on staying in front of Fengtai District Detention Centre overnight as a protest.

The police had never met a lawyer who insisted on doing this.

On 13 October 2014, he was detained for “being suspected of supporting the Occupy Central Movement”. He was kept in custody in Daxing District Detention Centre for 99 days, went through some 200 sessions of interrogations – some of them lasting over 18 hours. He was handcuffed and his hands were badly swollen due to long interrogations.

During his detention, he stayed in a death row cell for some time. He could even feel death nearing. “On 30 December 2014, an inmate walked out of the death row cell where I stayed. For a moment, I felt like I was joining him” he said.

To him, death is not that terrible a prospect. He found that the authorities’ abuse of power and their torturing of innocent people to silence them was even more unbearable.

He believes the law is a means of promoting democracy.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party in China in November 2012 – which saw the rise of Xi Jinping as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party -, Yu has observed a rapid deterioration. The newly enacted Charity Law, National Security Law, Overseas NGO Management Law, are all excessively stringent laws. In his words, “China is ruling the country with draconian laws.”

2015 mass arrests of civil rights lawyers: the first lawyer who talked back

On 9 July 2015, Wang Yu, a lawyer from the Beijing Fengrui Law Firm who had represented defendants in many famous human rights cases, was taken away by the authorities. Her final phone message read: “At 3:00 in the morning, there was a sudden power cut at home, and then the internet connection also broke. I hear the sound of someone breaking my door…”.

This day is known as “Black Friday” among Chinese lawyers, with the arrest of Wang Yu marking the beginning of the so-called “709 mass arrests.” In the following four months, more than 300 lawyers, law firm personnel and human rights defenders in China were summoned, interrogated, restricted from leaving the country, placed under residential surveillance, arrested or forcibly disappeared.

During the mass arrests, Li Wenzu, wife of the arrested lawyer Wang Quanzhang, asked Yu Wensheng to serve as Wang’s defense lawyer. However, Wang Quanzhang was not allowed to meet or communicate with Yu the whole time. As his defense lawyer, Yu was kept entirely in the dark. This practice completely violates just legal processes.

Xu Yan, Yu’s wife, remembered how he was under huge pressure at that time. He tried his best to help his client Wang Quanzhang, but the State security police officers of Shijingshan District prevented him from going to Tianjin city to see Wang. The State security police officers parked vehicles around their building to monitor Yu’s movement. Yu managed to escape one night and reached Tianjin overnight, but the authorities in Tianjin still refused to allow him to see Wang. His professional license and his application to start his own law firm were revoked and turned down respectively.

Yu was not detained in the first few weeks of the arrests, but not long afterwards, on 30 July 2015, he started a case against the Ministry of Public Security and its Minister for the illegal arrests. He is known as the first lawyer who fought back. His legal action angered the public security department and led to retaliation. In the evening of 6 August 2015, police came to his door. He refused to let them in, asking them to provide the legal documentation to enter. Instead of coming back with a warrant, the police broke into his apartment with an electric saw. Several dozen police officers rushed in, handcuffed him behind his back and took him away in front of his young son. He was kept in custody for 24 hours, 10 hours handcuffed behind his back and 14 hours handcuffed in front. He was forced to sit the whole time, with only short toilet breaks.

After the mass arrests of lawyers in 2015, Yu had a chance to leave China.

He once said, “there must be some people making a sacrifice; to pave the way for future generations. Since I have gone so far, I have no return, I don’t want to step back. So let me keep going, till genuine democracy and freedom reach China.”

Openly calling for constitutional reform

On 18 October 2017, on the opening day of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Yu Wensheng published an open letter, recommending the dismissal of Xi Jinping at the Congress and the comprehensive implementation of political reform. The police took him away that same evening and questioned him for over four hours.

In January 2018, Yu Wensheng published an open letter titled “A Citizen’s Proposal to Amend the Constitution”, advocating for political reform and democratic measures for electing the State leader. He was immediately detained by the police and has been denied his freedom since.

The prosecutor returned Yu Wensheng’s case to the Public Security Bureau for additional investigation on 20 November 2018. This is a process by which China’s criminal law allows prosecutors to refer cases to the police for additional investigation. This measure is often adopted in cases involving human rights defenders in order to prolong their detention.

Though he was born in Beijing and lived there all his life, since his arrest in 2018 Yu has been detained in Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province – nearly 450 miles away.

For Xu Yan, the saddest fact is that Yu Wensheng’s name is blocked and blacked out on the Chinese Internet. No one in China can find him online. His Weibo [a Chinese microblogging website often compared to Twitter], WeChat [the most popular chat app and online platform in China] and other social media accounts are all blocked. Even Xu Yan’s own social media accounts are blocked. Any article that includes Yu Wensheng’s name cannot be posted online. She has to put symbols between his name to tell others about Yu and it is very difficult for others to speak about Yu Wensheng as well.

In early February 2019, the procuratorate charged Yu Wensheng with “inciting subversion of State power”. In May 2019, Yu Wensheng was tried in secretin the Xuzhou City Intermediate People’s Court. The authorities hired two defence lawyers for Yu without notifying his wife. The court did not post a notice of the trial on the website as required by law.

In other words, no one from his family or friends were informed of the trial. On 17 June 2020, he was sentenced to four years in prison, and deprived of his political rights for three years. He immediately appealed after hearing the verdict at court, but his appeal was dismissed in December of the same year, with the original sentence upheld.

Since Yu’s detention, his wife has been denied the right to visit him. It wasn’t until January 2021, three years after his initial imprisonment, that Xu Yan was allowed to see her husband, via video-call, for the first time. She noticed that Yu Wensheng had lost his teeth, his right hand was shaking so badly that he could not write, and he looked pale and malnourished.

During her subsequent visits, she learned that he had suffered from starvation; was often made to sit in the same position for the whole day; he was forbidden from communicating, shopping in the prison and restricted from reading books.

She demanded that Nanjing Prison guarantee Yu Wensheng’s right to outdoor exercise, medical treatment, and to buy more food in the prison. Her most recent demand is to get Yu released on 1 March 2022, in accordance with the law. She hopes that then he can finally return to his home in Beijing to be reunited with her and their son.

In January 2022, she pleaded to the authorities to allow Yu to visit his dying father. But as with her previous requests, the request was denied and Yu was prevented from seeing his father for a final time.

Yu Wensheng once said that, “if someone is guilty, they should be convicted; if they are innocent, they should be released.” This is his definition of the rule of law. However, the authorities chose to send him, an innocent lawyer, to prison in order to make him give in and obey – but he is someone who never yields.

This story was written by The 29 Principles. Read more stories in our series of Chinese lawyers’ profiles here.

Join us and call on Chinese authorities to #FreeYuWensheng on 1 March 2022!

ISHR and nine human rights groups urge in a joint statement the Chinese government to ensure lawyer Yu Wensheng is able to leave Nanjing Prison and freely reunite with his family in Beijing.

Add your voice here!