Iran: Human Rights Council must convene a special session

Fifty organisations urge the UN Human Rights Council to urgently convene a special session to address an unprecedented escalation in mass unlawful killings of protesters in Iran.

The UN Human Rights Council president Coly Seck announced in February 2019 that he would seek the views of all stakeholders regarding the General Assembly’s consideration of the status of the Council between 2021 and 2026. ISHR's Human Rights Council advocate, Salma El Hosseiny, highlights how the Council can be strengthened without the need for institutional changes.

What is the desired outcome of elevation of the status of the Council to a primary organ of the UN?

Most will agree that the objective would be to strengthen the Human Rights Council’s contribution to the improvement of the human rights situation on the ground.

While recognising the political difficulties in an amendment to the UN charter, theoretically, elevation of the Council can have a normative effect.

If the UN’s primary human rights organ is considered an inferior body to, for example, the UN’s primary security organ, then human rights will be considered as secondary to security, both by UN bodies and programmes as well as by States themselves. The Council as a primary organ could also contribute to more prioritisation of funding for human rights.

But, is that enough for the Council to fully achieve its mandate and overcome the key challenges it faces?

No, it is not enough because the status of the Council is not the primary problem.

Its status as a subsidiary body though is indicative of the problem, which is lack of sufficient political will by States to prioritise human rights over political and economic interests. And conversely, the lack of political cost for States who continue to commit gross human rights violations, and in particular Council members.

So, if discussions about this issue are limited to changes within the UN system only, then it would be a missed opportunity. Instead, we should use this opportunity to ask how we can generate more political will for prioritising human rights in States’ national and foreign policies, and how to ensure that human rights win in the balance of political, economic and security interests.

Addressing this challenge is key to ensure that the Council responds promptly and effectively to address human rights violations, wherever they occur.

ISHR, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and HRCnet organised consultations with human rights defenders working at the national and regional levels, as well as States and OHCHR, to discuss how the Council can be strengthened from the ground up, meaning, from the perspectives of the primary beneficiaries of its work.

Participants acknowledged the important and valuable actions the Council has taken in fulfilling its mandate. Indeed, the last Council session in September 2018 was arguably the most successful session in its history: it created an independent investigative mechanism for accountability on Myanmar, it continued to shine a light on the war in Yemen, renewing the mandate of the Group of Eminent Experts, and it adopted a resolution on Venezuela, ensuring that the humanitarian crisis in that country would be subject to dedicated and sustained international scrutiny and pressure in 2019.

Yet participants also identified key challenges facing the Council and proposed solutions that would not require any institutional changes. Rather, these solutions only require States to demonstrate principled leadership. In other words, to improve by doing.

This year marks the 5th anniversary of the death of Chinese defender Cao Shunli. She died after she was denied medical attention in detention. She was detained because she engaged with the Council.

Egyptian defender Ibrahim Metwally remains in prison since September 2017. He was arrested and tortured for engaging with the Council’s mechanisms.

Saudi defender Samar Badawi was banned from traveling in 2014 to prevent her from engaging again with the Council. She is now imprisoned alongside dozens of other women human rights defenders, only because they fought for their right to exist equally as men in their country.

If Council members can detain, torture and kill people whose only “crime” was seeking to engage with the Council, shouldn’t they at least be held accountable by the Council itself?

They should, but they are not.

During the opening segment of this Council session, high-level State representatives affirmed their commitment to promoting and protecting human rights and civil society. But for their statements to be genuine, they must be translated into actions.

Indeed, States have made efforts to overcome the challenges of politicisation and selectivity of the Council, committing to address country situations in line with objective criteria. Yet, States are unwilling to initiate Council action and to take leadership on countries like China, Egypt and Bahrain, among other situations, and this is not an exhaustive list.

So if the Council won’t hold its members accountable, then who will?

As to the technical aspect of the question: before the General Assembly “considers again the question of whether to maintain this status”, it is clear from the text that there is no review of the Human Rights Council, but rather it is a consideration by the General Assembly of whether the Council should be elevated to the position of a primary organ of the UN, or should remain a subsidiary body of the General Assembly.

The General Assembly resolution 65/281 did not intend nor mandate a review of the Council, and given the current political context and dynamics, a review of the Council is not desirable.

If I were a State that was intent on diminishing the effects of the Council because I don’t want the Council to review my situation if it is already on the agenda or it should be, such as the ones I mentioned above, I would push for a comprehensive review. I would push for extensive discussions in Geneva and for the question to include what was not mandated, and that is a review of the work of the Council, for the following reasons:

First, extensive discussions in Geneva would occupy the Council and drain its resources to inhibit it from focusing on the substantive issues: addressing situations of human rights violations. This drain on resources disproportionately affects civil society who would have to take time from advocating for accountability for human rights violations, to advocating to get a seat on the table.

Secondly, opening up the question of reviewing the work of the Council, including the institution-building package, means that civil society risks losing its current ability to effectively engage with the Council.

In order to avoid a scenario where the Council is distracted from delivering on its mandate and where civil society is kept out, while at the same time avoiding a vacuum where the General Assembly deliberates on questions without expert input, ISHR proposes that the General Assembly be aided in this deliberation by an expert report, prepared jointly by the Secretary-General and the High Commissioner, with inputs from States, civil society, national human rights institutions and other relevant stakeholders.

A similar approach was used in the Secretary-General’s report on the UN’s implementation of the Declaration on human rights defenders, which was presented at the last session of the General Assembly. This approach would best ensure that the Council is able to focus its energy and resources on delivering on its mandate, while the General Assembly is guided, so far as possibly, by an expert and evidence-based approach, as against a wholly political approach, to answering the question.

This piece was adapted from on a speech delivered on 6 March 2019 at an event organised by the Universal Rights Group.

Fifty organisations urge the UN Human Rights Council to urgently convene a special session to address an unprecedented escalation in mass unlawful killings of protesters in Iran.

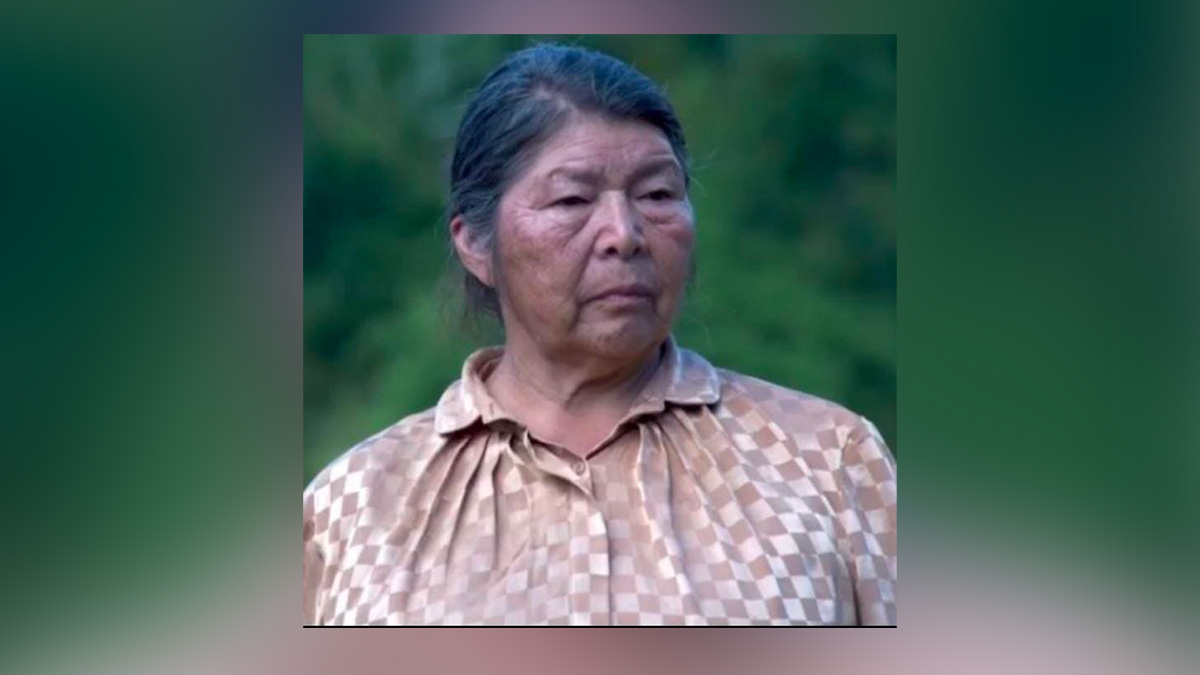

The Escazú Ahora Chile Foundation, the Protege los Molles Foundation and ISHR demand that the investigation, arrest and legal proceedings involving Julia Chuñil's relatives be conducted in accordance with international standards of due process.

At a time of financial strife and ongoing reform for the organisation, States have adopted a 2026 budget cutting 117 jobs at the UN’s Human Rights Office. The final budget endorses proposed cuts that disproportionately target human rights, imperilling the UN’s ability to investigate grave abuses, and advance human rights globally.