Egypt: Reform unjust vice laws, guarantee open civic space

During Egypt's UPR adoption at HRC59, Nora Noralla delivered a joint statement on behalf of ISHR, Cairo 52 and Middle East Democracy Center. Watch and read the full statement below.

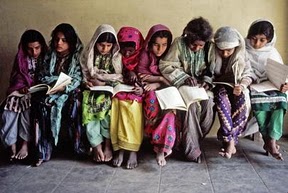

African, Islamic, Arab and Caribbean States of the Third Committee of the General Assembly united on 25th October to reject the final report of the previous Special Rapporteur on education, Mr Vernor Muñoz. Drawing on the work of several UN treaty bodies, the report recognised the human right to ‘comprehensive sexual education’, including reproductive health education. It also elaborated on the obligation of all States to ‘ensure that the gender dimension, human rights, new patterns of male behaviour, diversity and disability’ were included in the curriculum for sexual education from primary school onwards.

African, Islamic, Arab and Caribbean States of the Third Committee of the General Assembly united on 25th October to reject the final report of the previous Special Rapporteur on education, Mr Vernor Muñoz. Drawing on the work of several UN treaty bodies, the report recognised the human right to ‘comprehensive sexual education’, including reproductive health education. It also elaborated on the obligation of all States to ‘ensure that the gender dimension, human rights, new patterns of male behaviour, diversity and disability’ were included in the curriculum for sexual education from primary school onwards.

Amongst other things, Mr Muñoz was accused of exceeding his mandate and ‘flouting’ multiple provisions of the Code of Conduct for special procedures of the Human Rights Council. Several States also criticised him of ‘indulging in a twisted interpretation’ of the work of treaty bodies that would ultimately harm children and undermine the family unit. Most States disagreed that there was a human right to sexual education.

Only five States supported the Special Rapporteur and welcomed his preparedness to tackle these sensitive issues in his report (Canada, Costa Rica, Liechtenstein, Norway, Sweden). In a particularly supportive statement, Sweden said it was convinced that comprehensive sexual education would help address negative gender stereotypes, empower women, combat HIV AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, and contribute to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Costa Rica, perhaps in response to the concerns expressed by the Holy See, added that the Special Rapporteur’s recommendations affirmed the role of the family and the State, rather than undermined them.

Other States, including the EU, agreed that comprehensive sexual education was important to enable women and girls to enjoy a range of other human rights, but did not refer to it as a human right. Rather, they affirmed the need for all special procedures to be able to carry out their work with full independence and free from interference from States (Australia, EU, UK). Rather than ‘ceaselessly attacking’ special procedures, Switzerland reminded the Committee that these experts were ‘the cornerstone’ of the UN human rights system. It was only natural that they would sometimes hold different views to States, and States should respect the role of the Coordinating Committee for special procedures to provide the necessary level of oversight of their work.

The US did not refer to the independence of the Special Rapporteur, but disagreed that there was a right to sexual education. Along with many other States (African group, Arab group, CARICOM, South Africa), the US regretted that the Special Rapporteur had missed a timely opportunity to provide expert guidance on how States could achieve MDG goals 2 and 3 that relate to universal education and gender equality.

The new Special Rapporteur, Mr Kishore Singh, who presented the report, declined to speak to its contents or respond to the concerns raised by States. Instead he focused on his priorities for the mandate. Nonetheless, Mr Singh undertook to convey the comments to the previous mandate holder. At the conclusion of the interactive dialogue, the Chairperson, Mr Michel Tommo Monthe (Cameroon) advised that “if answers come, the Third Committee will consider them. Otherwise we will let this report rest in peace”. However, given that Mr Munoz no longer holds an official position within the UN system, it is unclear in procedural terms, how he could submit a response to the Third Committee. It therefore seems more likely that Mr Munoz’s report will conveniently be shelved, as has been the case with the reports of other special procedures who sought to raise the controversial matter of sexual orientation and gender identity in the General Assembly in the recent past.

Malawi (on behalf of the African Group) led the charge against the report of the Special Rapporteur. The detailed criticisms included that the previous mandate-holder had sought to: over-step the terms of his mandate; introduce ‘controversial concepts’ that were not recognised under international law; create new human rights; relied on information from non-credible sources that was not verified; failed to incorporate information provided by Member States; selectively quoted from the work of the treaty bodies in a manner that distorted their views; and sought to propagate controversial principles (the Yogyakarta Principles) that were not endorsed at the international level. Each of these criticisms was in contravention of the Code of Conduct and if left unchecked, would undermine the entire system of special procedures. Further, the mandate-holder should have first sought the consent of the Human Rights Council before undertaking the report, and should have first reported to the Council, not the General Assembly. Finally, in deviating so far from his mandate, the Special Procedure had deflected States’ focus from the core challenges that had to be overcome if States were to meet the MDGs and improve the enjoyment of the right to education.

Other States and political groups which echoed these views included: Trinidad and Tabago (on behalf of the Caribbean Community or CARICOM); Mauritania (on behalf of the Arab Group); Morocco (on behalf of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference).

A number of other States also criticised the Special Rapporteur. Although the Russian Federation opposed discrimination on any grounds, it could not agree that there was an inalienable right to sexual education, nor condone the use of concepts that were disputed at the international level. Further, Russia did not approve of the Special Rapporteur’s references to the ‘so-called’ Yogyakarta Principles, which had not been agreed at the inter-governmental level. It warned that if implemented, the Special Rapporteur’s recommendations would result in the ‘corruption of minors.’

South Africa expressed dismay at why the previous Special Rapporteur had ‘deliberately ignored and undermined his mandate.’ It was critical of the ‘disjointed and confusing approach’ he had taken, which wrongly linked the right to education with the right to health. In South Africa’s view, issues of health were outside the mandate on education. In another veiled swipe at the Yogyakarta Principles, South African urged new Special Rapporteur to be guided by the internationally agreed human rights framework.

The Holy See also took issue with the Special Rapporteur and his report. It argued that the family was the natural and fundamental group unit, referring to its status as an ‘institution’ where children learn values and are initiated into the wider society. Referring to the work of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Holy See reminded States that parents have the ‘primary responsibility’ to determine what is in the best interests of their child. In its view, the report was an attempt to create a division in this relationship that would only ‘damage’ children, parents, marriage and the family.

During Egypt's UPR adoption at HRC59, Nora Noralla delivered a joint statement on behalf of ISHR, Cairo 52 and Middle East Democracy Center. Watch and read the full statement below.

The 59th session of the UN Human Rights Council (16 June to 9 July 2025) will consider issues including civil society space, climate change, sexual orientation and gender identity, violence and discrimination against women and girls, poverty, peaceful assembly and association, and freedom of expression, among others. It will also present an opportunity to address grave human rights situations including in Afghanistan, Belarus, China, Eritrea, Israel and oPt, Sudan, Syria and Venezuela, among many others. Here’s an overview of some of the key issues on the agenda.

On 4 May 2025, on the sidelines of the 83rd Ordinary Session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) in Banjul, ISHR officially launched its new report on the situation of human rights defenders in the African island states: Cape Verde, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Seychelles.