Groundbreaking in their conceptualization, the Yogyakarta Principles are a milestone in the establishment through law and precedent that all human rights are for all – without exception.

Ten years ago, a distinguished group of human rights experts from around the world came together at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. They met to provide victims of human rights violations based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) an authoritative legal tool with which to seek justice and protection.

The outcome is perhaps the most significant international legal development in SOGI history.

The 29 principles are a universal guide on existing human rights law as it applies to sexual orientation and gender identity. They affirm binding international legal standards, and have contributed enormously to the development of jurisprudence, laws, policies and practices to address the discrimination and violence faced by people based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

They have directly impacted on the lives of LGBT people in numerous ways. For example:

- Argentina’s 2012 gender identity law, which brought effect to the Yogyakarta Principles, provided trans people access to critical services without the need for medical intervention, sends a clear message against transphobic violence and affirms the rights and dignity of trans people.

- The UN High Commission for Refugees released guidelines on the protection of refugees based on SOGI citing the Yogyakarta Principles. As a result, increased numbers of LGBT people have been granted reprieve from threats, attacks and violence at home.

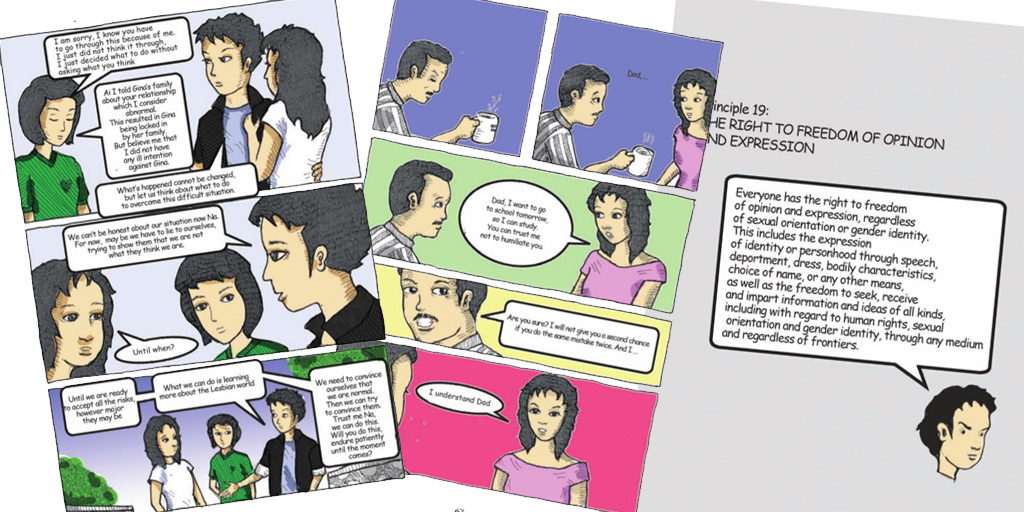

- The Principles have been an important toolkit for defenders of LGBT rights – even making their way into a comic book initiated by the Institut Pelangi Perempuan.

Placing sexual orientation and gender identity on the same plane

The phrase ‘SOGI’ now rolls off the tongue quite easily. Yet, before the Yogyakarta Principles were formulated, the language in international law focused solely on sexual orientation.

‘Gender identity’ found its way into the principles due to the sustained advocacy by LGBT defenders from the global south for whom such an inclusion was a non-negotiable. Since then, the concept of gender identity has made its way from the Yogyakarta Principles into judicial decisions made at the national level, as seen by the NALSA v Union of India decision on trans rights by the Indian Supreme Court which affirmed that India’s Constitutional rights are equally applicable to trans people, and gave them the right to self-identify their gender.

Providing definitions of sexual orientation and gender identity

Surprising as it is, none of the legal decisions which preceded the Yogyakarta Principles actually ventured into the terrain of defining sexual orientation or gender identity. We owe it to the experts at Yogyakarta for setting out a legal definition which has since been quoted verbatim in judicial decisions and policy documents and used extensively by human rights defenders around the globe.

Developing the right to recognition before the law

Principle 3 provides for recognition before the law. This principle emerged in international human rights law out of the struggle against Nazi ideology whereby Jews were stripped of legal identity and citizenship, rendered non-citizens with no rights. The innovation which Principle 3 introduces is to take that right and apply it to the specific context of gender identity and sexual orientation.

Legal systems around the world routinely deny trans persons legal recognition of their gender, in large part because they fail to acknowledge the fundamental notion of the right to define one’s gender. Since the Yogyakarta Principles were adopted, Argentina, Ireland and Malta have moved closest to implementing this Principle in their laws enshrining the right to self-determination of gender.

Right to privacy

The right to privacy is normally seen as the right not to be interrupted in the peaceful enjoyment of one’s home. Principle 6 crystallises this by also including ‘decisions and choices regarding both one’s own body and consensual sexual and other relations with others’ within the understanding of the right to privacy. Thus Principle 6 takes privacy beyond the notion of ‘zonal privacy’ to also include ‘decisional privacy’ and ‘relational privacy’. This means that when we say that anti-sodomy laws violate the right to privacy, we are asserting that forming intimate ties with others of the same sex is part of the right to autonomy and an inalienable part of one’s dignity.

Protection from medical abuse

While the law, state and society may be key violators of rights on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity, Principle 18 draws attention to the role of medicine and the medical establishment as potential violators of human rights. As Principle 18 notes, ‘a person’s sexual orientation and gender identity are not, in and of themselves, medical conditions and are not to be treated, cured or suppressed,’ alerting us to the human rights violations which follow from the classification of sexual orientation and gender identity as medical disorders.

Ten years of the YP: Looking ahead

We recognize the advances made in this past decade with the important contribution of the Yogyakarta Principles. As we look forwards, a few elements for further development remain key.

The Principles were intended to be a snapshot of status of international human rights law of the time. Today, the LGBT and intersex communities note a number of jurisprudential developments that have gone some way in ensuring recognition and protection of LGBTI people. In particular, the right of intersex infants not to be subjected to medically unnecessary interventions, the rights of trans sex workers and the rights of LGBT refugees require further specific elaboration within the framework of the established principles.

Furthermore, while the Principles affirm established international human rights standards and principles, they remain in themselves non-binding. Giving the Principles enforceability depends on national implementation, greater sensitization and support from judicial decision-makers and policy-makers and continued innovation by civil society.

Arvind Narrain is ARC International’s Geneva Director and Pooja Patel is ISHR’s Human Rights Programme & Advocacy Manager