Human rights defenders, access to justice and the rule of law

The work of human rights defenders (HRDs), including lawyers and judges, is vital to promoting and upholding equality, access to justice and the rule of law at the national and international levels; in other words, to achieving SDG 16 and particularly SDG 16.3.

Yet despite this vital role, HRDs are under what the UN Special Rapporteur on HRDs has called ‘unprecedented attack’, ranging from legal restrictions, to defamation, arbitrary detention, disappearance and even death.

To some degree this is reflected in SDG indicator 16.10.1, which relates to the ‘number of verified cases of killing, kidnapping, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention and torture of human rights advocates in the previous 12 months’.

HRDs working in the justice sector are particularly vulnerable, with the UN Special Rapporteur identifying lawyers and those working to combat impunity and promote accountability for gross human rights violations as being among those most at risk.

The Special Rapporteur and other experts have also identified the specific recognition and protection of HRDs in national law as a key factor contributing to a safe and enable environment for their work and, by extension, to equal access to justice for all.

In this context, and on the eve of the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders by the UN General Assembly by consensus in 1998, it is timely to consider the extent to which the international Declaration is being used by domestic and regional courts to interpret and apply domestic and regional law to enhance the protection of defenders and, thereby, access to justice and the rule of law.

European jurisprudence

Notwithstanding the difficult, dangerous and deteriorating environment for defenders in European States including Azerbaijan, Hungary, Russia and Turkey, neither European national courts nor the European Court of Human Rights have used the Declaration as an aid to the interpetation or development of national or regional jurisprudence.

To be fair, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights has filed a number of recent third party interventions in cases against Russia and Azerbaijan in the European Court of Human Rights relying on the Declaration to elaborate States’ obligations to respect and protect the right to life of HRDs. These submissions have expounded the vital role of HRDs, including judges and lawyers, in ‘ensuring access to fair and impartial justice’. Judgments have not yet been rendered in most of these cases, although in the one that has, Rasul Jafarov v Azerbaijan (2015), the Court did not cite the Declaration in its reasons.

Latin American jurisprudence

The jurisprudence is more evolved in Latin America, both at the regional and national levels.

At the regional level, the Inter-American Court has explicitly recognised the work of HRDs as being ‘fundamental for the strengthening of democracy and the Rule of Law’ (see, eg, Valle Jaramillo v Colombia, Castillo González v Venezuela).

In a series of recent judgments (see, eg, Human Rights Defender et al. v Guatemala (2014) and Luna Lopez v Honduras (2013)), the Inter-American Court has relied on the Declaration to affirm that the right to defend human rights is a fundamental right that must be respected and protected.

The Court has used the Declaration as a significant interpretative aid, particularly with respect to the scope and application of the right to life, security and liberty of defenders. Thus, these rights have been interpreted by reference to the Declaration to require that:

- States create the conditions that are necessary for HRDs to freely carry out their activities

- States refrain from hindering HRDs’ work

- States take ‘special measures of adequate and effective protection’ where a defender is at risk. Such measures should be designed to enable the HRD to continue their vital work and be gender sensitive. Measures should respond to both individual and systemic risk factors.

- States must thoroughly and effectively investigate violations against HRDs. The Inter-American Court has recognized that attacks and restrictions against defenders are particularly grave because they have both an individual and collective impact. The Court has also recognised that impunity for violations is a significant factor contributing to violations and undermining the rule of law.

See, eg: Human Rights Defender et al. v Guatemala (2014); Luna Lopez v Honduras (2013); Castillo González v Venezuela (2012); Nogueira de Carvalho v Brazil (2006)

At the level of national courts in the Latin American region, a number of recent decisions have called on the Declaration as an interpretative tool to strengthen the protection of HRDs under national law.

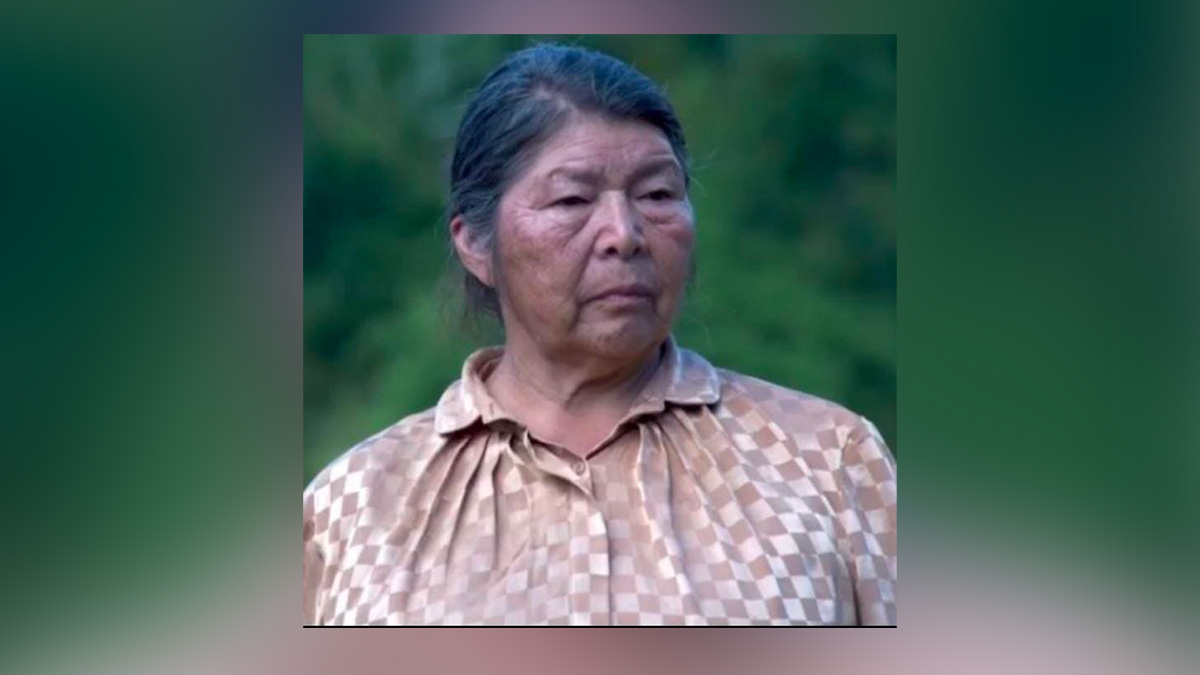

In Decision T-234/12 of 2012, relating to an application for protection measures by a woman human rights defender subject to sexual violence and kidnapping, the Constitutional Court of Colombia held that the Declaration, although not legally binding, ‘constitutes an important interpretation tool’. The Court drew on the Declaration to interpret the Colombian Constitution and various international instruments, such as the ICCPR, which are incorporated into Colombian law pursuant to Articles 93 and 94 of the Constitution. In the outcome, the Declaration was relied on to support a ruling that the State should adopt specific protection measures which took into account the status of the petitioner as both a woman and a human rights defender.

In a 2016 decision, Constitutional Challenge 87/2015, the Supreme Court of Justice of Mexico held that the Declaration, while not itself legally binding, does elaborate a set of principles and rights that are based on legal standards enshrined in other international instruments, including in relation to the right to freedom of expression and information. This supported a ruling striking down provisions of a state law restricting the access and activities of journalists.

African jurisprudence

Turning to another region, Africa, a small number of recent regional and national decisions have similarly drawn on the Declaration as an authoritative interpretative aid.

In the case of Law Offices of Ghazi Suleiman v Sudan (2013) – a lawyer who was denied the right to travel to deliver a lecture – the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights cited the Declaration in support of the principle that: (1) a HRD’s speech is directed towards the promotion and protection of human rights, (2) is therefore of special value to society, and (3) is therefore deserving of special protection.

The High Court of Nairobi case of Eric Gitari v Non- Governmental Organisations Co-ordination Board & 4 others [2015] concerned the refusal of a public authority to register an NGO advocating for LGBTI rights and equality. While recognising that the Declaration is not legally binding, the Court opined that it can and should be used by States to determine how existing human rights laws and standards apply to defenders. Subsequently the Declaration was cited to support the proposition that Article 36 of the Kenyan Constitution protects the right of LGBTI persons to form non-governmental associations.

National HRD laws

In addition to using the Declaration as an interpretative aid, a number of jurisdictions in both Latin America and Africa – including Mexico, Honduras, Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Mali – have enacted, or are in the process of enacting, legislation incorporating the Declaration into national law. While clearly not a panacea to the ‘unprecedented attacks’ against defenders, these laws are a step in the right direction, with a recent report by the Swiss Government associating Cote d’Ivoire’s 2014 Law on the Promotion and Protection of HRDs with a significant decline in attacks against defenders in that country.

ISHR is pleased to have contributed to the development of the law in Cote d’Ivoire and other jurisdictions through our Model National Law on HRDs, developed and adopted by a panel of 28 eminent human rights experts in 2016.

Conclusion

The work of HRDs is vital to good governance, accountability, sustainable development, and equal justice for all.

Despite this, HRDs, including those working in the justice sector, are facing worsening restrictions and attacks.

Human rights defenders’ legal recognition is a vital factor contributing to their practical protection and a safe and enabling environment for their work. We have, in international law, a Declaration adopted almost 20 years ago, articulating fundamental principles and standards in this regard. It is, however, significantly lacking in implementation and justiciability at the national and regional levels. Whether you are a lawyer arguing cases, a judge determining cases, or a policy maker or legislator drafting law, I urge you to do what you can to incorporate the Declaration into national law.