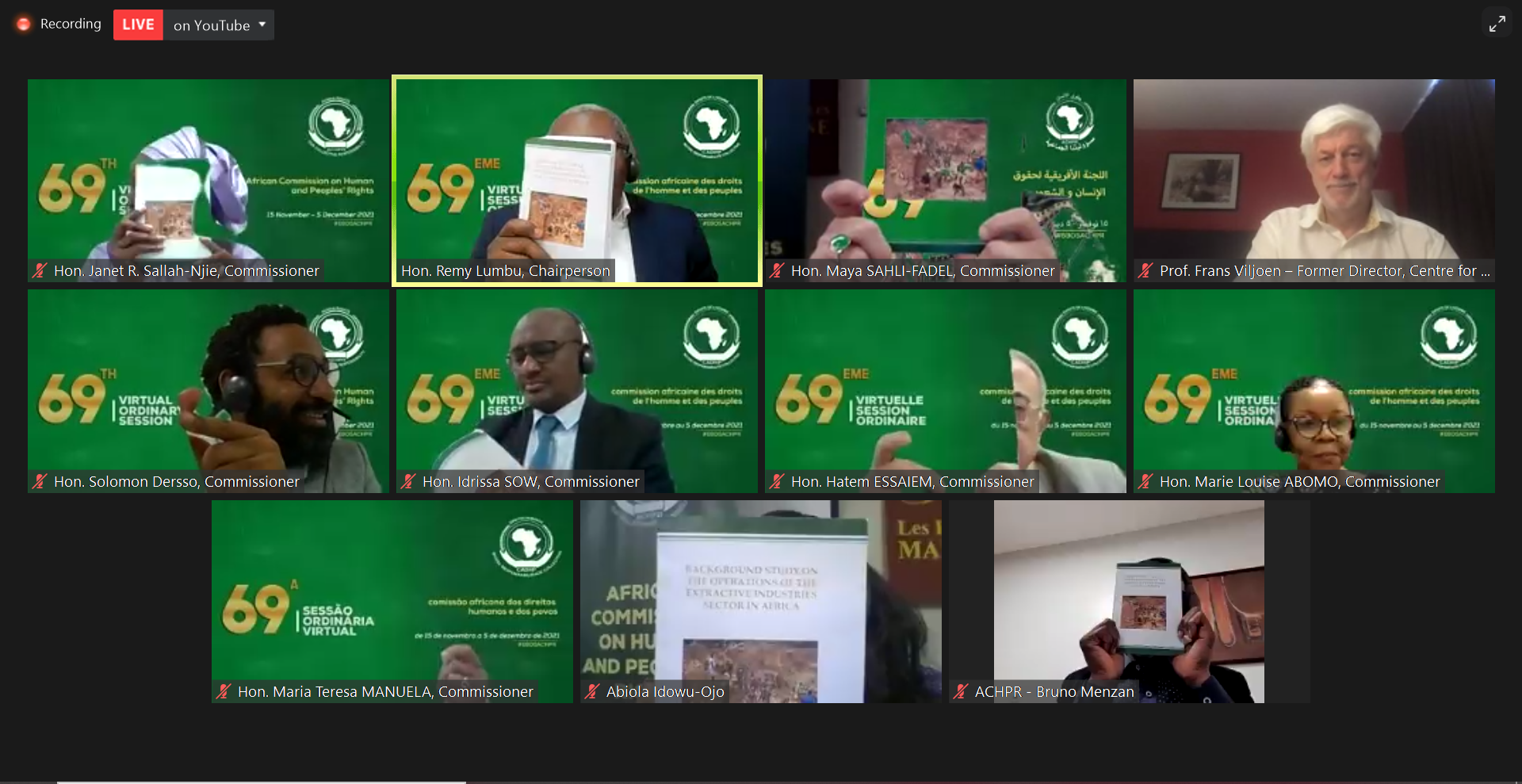

On Tuesday 23 November 2021, the African Commission held a panel discussion on the new study on extractive activities and their impact on the enjoyment of human rights. The study is based on field visits across the continent from 2013 to 2019. It reveals the damning extent of the perverse effects of extractive industries’ activities across Africa. Beyond the human rights impacts, extractive industries activities pose a public health and security problem as they affect a majority of fundamental rights such as the right to water, the right to land, the right to decent work, it impacts on the rights of women and children, and sometimes even the right to life. Increasing cases of human rights violations, retaliation and violence against defenders, resource-related terrorist conflicts and illegal cash flows that are rooted in extractive activity demonstrate the wide-ranging and multidimensional consequences that communities in Africa face.

These abuses and violations are caused, among other things, by management that is primarily aimed at protecting the business of extractive companies, which is the result of deeply unequal bilateral agreements between countries and extractive companies that benefit only the latter.

The study also points to the continent’s structural, historical and colonial causes of looting and resource theft, the disparities in economic and bargaining power between countries and multinationals, and the legal vacuum regarding corporate activities in African territory. Coupled with this, the extractive sector has acquired powerful economic, social and political influence in Africa to override legal and state powers. As a result, accountability of extractive companies when they fail to meet their Corporate Social Responsibility commitments or when human rights violations occur is difficult, if not impossible. Sanctions, when they exist, are derisory and have no impact on the continuity of the company’s activities. Human rights defenders and environmental activists who attempt legal actions often face a strategy used by extractive companies which consist in burdening them with the cost of legal defense until they abandon their charges. Cases of harassment and murders of defenders were also present in the report, which underscored the vulnerable position they have and how limited their room of manoeuvre is when facing the extractive sector. In response, Commissioner Solomon Ayele Dersso, Chairperson of the WGEI, stated that “what was once a potential source of economic development for Africa has now become a curse, the ‘resource curse'”.

For the WGEI, changing this dynamic requires a de facto radical change. It calls for a comprehensive review of the continent’s resource sector, aligned with articles 21 and 24 of the African Charter, which comprise the longest provisions and indicate the historical importance of involving African peoples in their resources. Secondly, it calls for the African Charter to be more consistent with the reality and power relations between States and multinationals. Indeed, until now, the obligations regarding human rights and the extractive sector have only been incumbent on the State. The WGEI therefore advocates making extractive companies as accountable as the country for the consequences of their activities and making this visible and explicit in the African Charter. To reinforce their work, the WGEI plans to expand its mandate to include the impact of big business in general on human rights and the environment in addition to the work on extractive industries. Finally, the activities of civil society, the role of defenders, more specifically environmental defenders, was welcomed and is, in this context, more crucial than ever in the fight for fundamental rights and justice.