As the next session of the Human Rights Council approaches, civil society organisations*, Guatemala human rights defenders and Indigenous representatives analyse the current human rights situation of Guatemala, including the stakes of the 2026 judicial system renewal process, the situation of human rights defenders, Indigenous Peoples, and access to land.

At this upcoming Council session, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) will be presenting its annual report on its activities in Guatemala and the Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing will be presenting his report and recommendations on his official visit in the country in July 2025. In addition to these recommendations, Guatemala should also implement the recommendations of the Special Rapporteur on the Independence of judges and lawyer’s visit last year and those of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Justice system

Since 2019, instances of criminalisation of justice operators have increased, particularly among those involved in anti-corruption cases. Between 2020-2025, the OHCHR office Guatemala has documented 206 attacks, including 66 cases of criminalisation. In an official visit, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers confirmed the systematic pattern of criminalisation against justice operators.

This year, Guatemala will renew the members of its Supreme Electoral Tribunal, the country’s Constitutional Court, and the Office of the Attorney General. The renewal will come amid continuous calls by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to ensure a process that guarantees new members’ selection is independent, transparent and based on merits and objective criteria. One of the main concerns with 2026 renewal process is that criminalisation creates a deterrent effect on qualified individuals who might otherwise be interested in applying, discouraging their participation. There are also significant risks of criminalisation and reprisals against members of the selection bodies during the 2026 renewal process, hence, it is important that these processes be conducted objectively and publicly. This would be an opportunity to restore the legitimacy of the Guatemalan judicial system and strengthen democratic institutions.

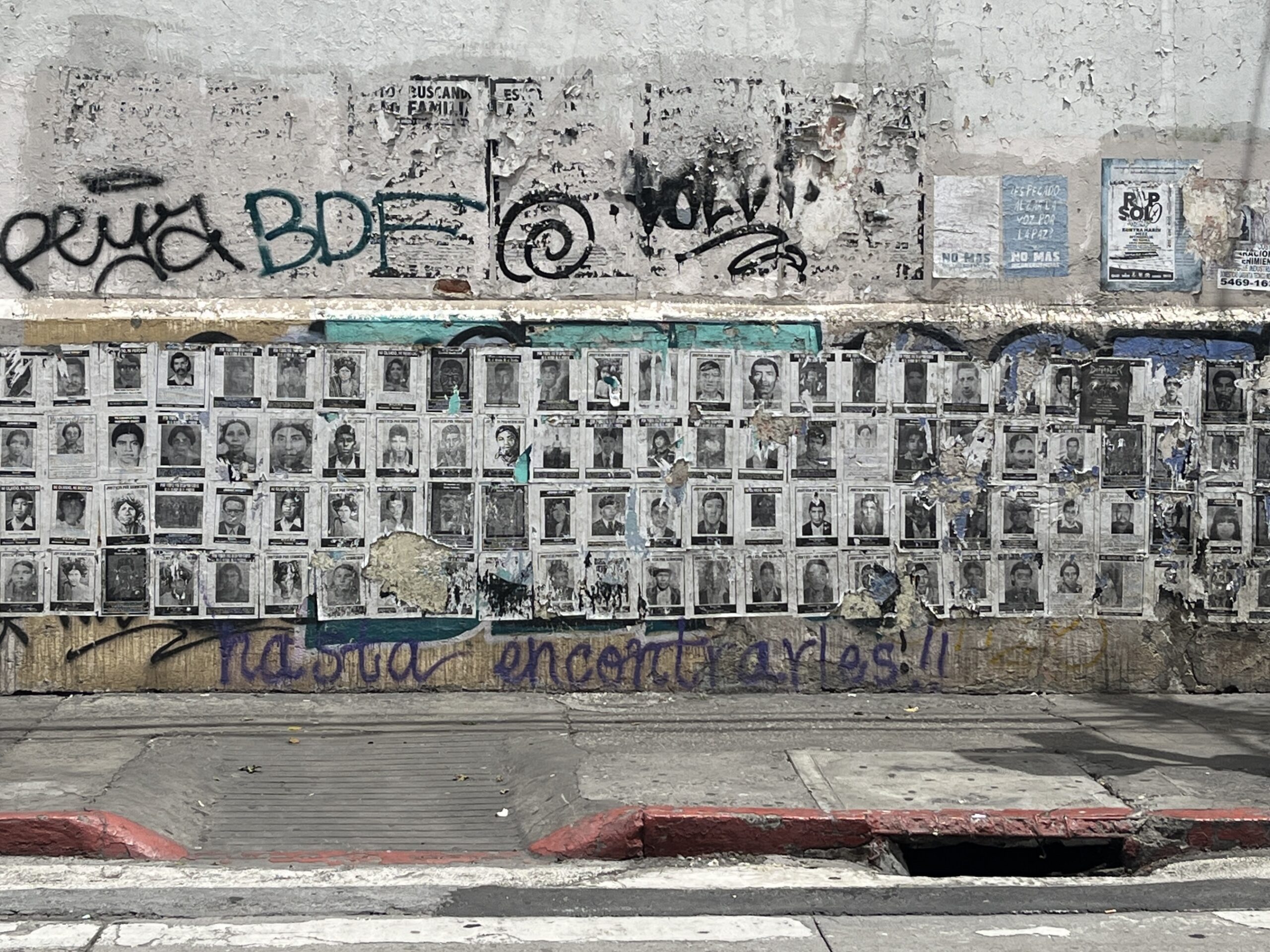

Situation of human rights defenders

The Human Rights Defenders Protection Unit of Guatemala (UDEFEGUA), a local watchdog, documented 4,520 attacks against individuals and communities exercising their right to defend rights between January and September 2025. Criminalisation strategies continue to intensify. This is evident in the prolonged imprisonment and deliberate delays in hearings for cases such as those of Indigenous leaders Luis Pacheco and Héctor Chaclán, and journalist José Rubén Zamora.

Other emblematic cases include Leocadio Juracán, a former congressman and leader of the Altiplano Peasant Committee,, Ramón Cadena a human-rights lawyer , and Basilio Bernardo Puac, an Indigenous leader who, along with Pacheco and Chaclán, led took part in the resistance against attempts to overturn the results of the country’s general election in 2023 . That same year, many other Indigenous, peasant, and student defenders—less publicly known— also faced criminal charges, some were even forced to go in exile.

In November 2025, Guatemala took a positive step by approving a protection policy for individuals, organisations, and communities defending human rights, though it still requires the creation of an implementaiton body.Guatemalan authorities must take steps to operationalise this policy and to implement an effective protection mechanism capable of preventing harm, ensuring protection, and providing reparations for human rights defenders. They must also report on the progress in implementing the policy by the end of 2026 as a follow-up to a recommendation from the Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD).

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous Peoples continue to face criminalisation, persecution, threats, and imprisonment for defending their rights within their territories. Several authorities and leaders remain tied to criminal proceedings based on unfounded accusations linked to business operations, including extractive industries.

The imposition of extractive projects in Indigenous territories continues to violate human rights, and despite existing judicial decision to stop operations, companies continue their activities.

In 2023, in a case involving a mining company in the municipality of El Estor the Inter-American Court on Human Rights found that the local Maya Q’eqchi community was not consulted according to international standards, the Guatemalan Constitution and in violation of a Constitutional Court ruling. To date, authorities have yet to abide by this ruling and conduct consultations, while the company continues its operations.

Guatemala stop must criminalising the work of Indigenous leaders and communities and comply with its international obligations and respect Indigenous Peoples’ right to free, prior and informed consent in such contexts.

Access to land and evictions

Guatemalan law still does not adequately recognise or protect the lands of Indigenous and Afro-descendant Peoples, and the responsible institutions—further weakened since 2024—are failing to comply with court rulings ordering the restitution of rights. Current regulations also do not acknowledge traditional forms of land tenure nor ensure free, prior, and informed consent.

In 2021, the Public Prosecutor’s Office created the Office of the Prosecutor for the Crime of Usurpation, responding to demands from the private sector. The mere presence of peasants on disputed lands could be suject to criminal charges, with penalties of up to six years in prison. Large landowners or companies can file complaints without exhausting administrative or civil avenues, leading to forced and often violent evictions.

In this context, forced evictions have increased in the Guatemalan departments of Petén, Alta Verapaz, Baja Verapaz, and Izabal where many evictions are conducted without notice and with disproportionate force, involving both public and private security, the burning of homes, crops, and personal property. Repeated violence may amount to cruel or degrading treatment.

The Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing and the CERD have urged Guatemala to immediately impose a moratorium on evictions until it can guarantee adequate legal protections and end the widespread practice of violent and inhumane forced evictions and criminalisation, particularly against Indigenous Peoples and rural communities.

*The following organisations contributed to the preparation of this analysis: Center for Justice and International Law, International Commission of Jurists, Due Process of Law Foundation, ISHR, Washington Office on Latin America, Peace Brigades International , Programa ACTuando Juntas Jotay, International Platform against Impunity and Protection International Mesoamérica.