This week there have been two interactive dialogues on Venezuela at the Human Rights Council: with the Deputy High Commissioner on 19 March, and with the members of the fact-finding mission (FFM) on 20 March. These took place in the context of the suspension of OHCHR activities in Venezuela when, on 15 February, the Venezuelan government gave the 13 members of the team 72 hours to leave the country.

Deputy High Commissioner Nada Al-Nashif expressed her ‘deep regret’ for the suspension of OHCHR activities and the wish that the Office could ‘soon be able to fully resume its work to serve people in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela…in strict compliance with the mandate of the Office’. There was no reference to engagement with the Venezuelan authorities as in an earlier communication from the Office. She spoke of positive changes that had been experienced with the Office within the country and that much remains to be done. For his part, the new Venezuelan Ambassador to the UN chose to call the Office ‘a neo-colonial law firm at the service of the US and its satellites’.

‘The OHCHR continues to push for a comeback but needs to be clear about its red lines,’ said Eleanor Openshaw of ISHR. ‘It is essential that it does not compromise on being able to fulfill a full mandate that includes documenting violations, reporting and working with civil society in the country.’

In its statement during the session, ISHR referred to the suspension of the Office fitting a pattern of increasing repression in the country.

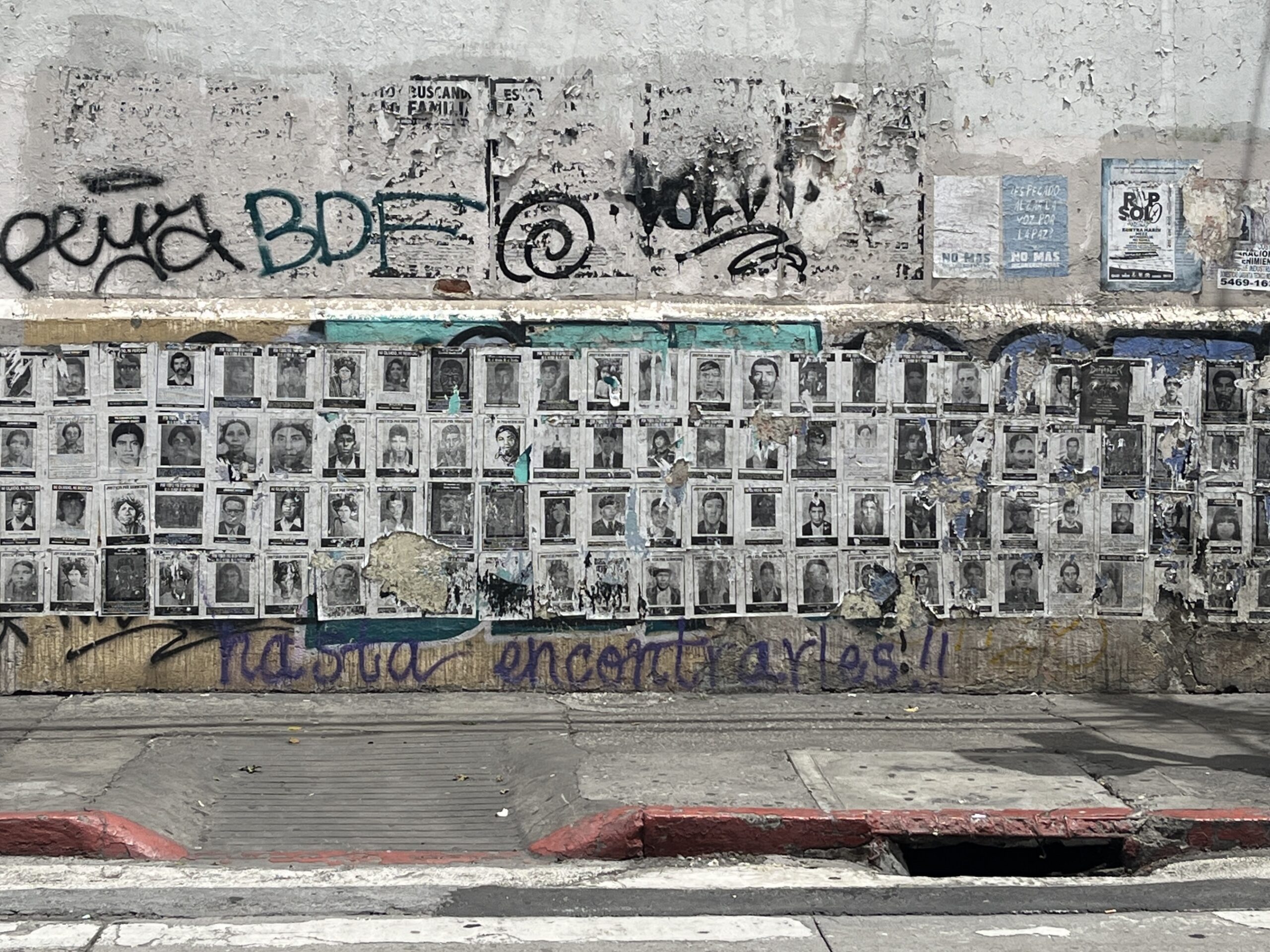

This upsurge of repression in the country was the focus of the FFM Chair’s oral update. Marta Valiñas commented that ‘we are facing a phase of reactivation of the most violent modality of repression by the authorities’ and that modality ‘is activated to silence the voices of the opposition at any cost, including through the commission of crimes’.

The FFM, the Deputy High Commissioner, and several States highlighted the increase in cases of intimidation, stigmatisation, and even detention of opposition parties, journalists, defenders and other dissenting voices – real or perceived, to the Maduro regime. Following the Human Rights Council session, Uruguay issued an appeal to Venezuela to release political prisoners. The cases of Javier Tarazona and Rocio San Miguel were on the lips of many during the session and the draft NGO bill was discussed as an example of a prevailing attempt to restrict the free and independent action of civil society.

Many countries in the room expressed their concern about the facts and, recognising the complementarity of the work done by both mandates, urged Venezuela to resume cooperation with the UN agencies.

To countries that spoke of Venezuela’s cooperation with the system, including Brazil, FFM member Francisco Cox said, ‘I don’t know how you cooperate with OHCHR by expelling it’.

The ambassador of Paraguay, in the interactive dialogue with the High Commissioner, responded to accusations of selectivity in the establishment of UN mechanisms in the case of Venezuela, asking: ‘What shows more selectivity than Venezuela’s choice not to cooperate with OHCHR, the FFM or the vast majority of independent experts?’

While several States of the region intervened through joint statements (Paraguay, Canada, Chile, Argentina, Guatemala, Ecuador; Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands; and all the core group States in another) or individually, the voices of Mexico and Colombia were missing in the space. Honduras spoke of UN mechanisms in Venezuela as an example of interference.

The dialogues ended with a recognition that in a pre-electoral context the risks for voices opposed to the State increase. In fact, the day after the dialogues concluded, Venezuelan security forces detained two more members of the opposition within presidential candidate Maria Corina Machado’s team.