Groundbreaking report from UN expert

In his report to the Human Rights Council’s 38th session, Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression David Kaye highlights the international legal framework for expression online, and notes both State obligations – namely that limitations be ‘legal, necessary, proportionate and legitimate’ – as well as company responsibilities in line with the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Obligation to protect…

The Special Rapporteur also presents a snapshot of how governments are shaping the environment for online speech, through regulations which may provide protections against credible threats and abuses, but which in some cases ‘rely on censorship and criminalisation’ to mitigate dissenting views; permit active dissemination of propaganda or disinformation; or displace obligations to restrict or monitor content onto companies themselves. The Chinese Cybersecurity Law is one example, which not only prohibits ‘false’ information, but requires companies to act as watchdogs, surveilling users and reporting alleged violations.

Global removals, or government demands on platforms or individuals to remove content even when posted outside national borders, are increasing. Requests for these removals are increasingly going through informal channels or through proxies. Pressure on Mercedes-Benz to remove a quote by the Dalai Lama used in advertising, or on the travel industry to ensure ‘appropriate’ references to destinations such as Taiwan and Tibet, are just a few recent cases.

…and responsibility to respect

Companies, too, are implicated in restrictions on free speech – even when their mission statements seem to support connectivity and conversation. Complying with national laws, themselves deeply problematic, is one way in which companies are complicit. WeChat, for example, seeks to extend content restrictions applicable within China to users ‘anywhere in the world’.

Company-produced standards and tools for moderating content are produced in a non-transparent way, subject to discretion by a range of stakeholders, and can put individuals, and in particular human rights defenders, at risk with demands like real-name registration. The report cites specifically Chinese provider Baidu as requiring personally-identifiable information in order to post publicly – the effectiveness of this as a means of minimising abuses is, the Special Rapporteur says, ‘questionable’. Systems for disclosing actions such as removals of content or closures of accounts, and the provision of appeal processes or remedy, are nascent at best.

Freedom of expression behind the Great Firewall

However, content moderation is just one of a string of challenges to the exercise of free speech in China. As evidenced in the extensive documentation in the report, and in a joint submission to the UN by ISHR and the Committee to Protect Journalists, harsh laws and regulations and escalating censorship technology risk completely excluding certain kinds of speech on the internet.

Access to information

Since the setup of the ‘Great Firewall’, it has become more and more difficult for Chinese residents to visit overseas websites. Today, overseas mainstream media and social media are almost completely inaccessible. Since 2015, the threat and incrimination of citizens who use unregistered VPNs to bypass the Great Firewall have become common. In 2017, one provider was sentenced to more than five years in prison for distributing VPN services. Also in 2017, Apple removed all VPN apps from its AppStore, citing the need to comply with domestic legislation.

Penalities and criminalisation

On the other hand, since 2016, the introduction of cybersecurity law and other regulations has made the control within the Great Firewall increasingly severe. Social media providers and market-oriented media were frequently the subject of official inquiries, asked to rectify certain ‘incorrect’ statements, and fined. This creates incentives for media companies and platforms to further engage in self-censorship and proactively (and arbitrarily) delete content. The provision of news services on blogs, social media, and instant messaging software has also been targeted with new requirements to apply for qualifications. Independent media, citizen journalists, and even normal Internet users publishing what they see and hear can be considered, now, ‘illegal’.

Faced with this double-sided attack, space for Chinese citizens to freely access information and participate in discussions has been severely squeezed. Social issues that require media attention and public supervision cannot enter the public view, and human rights violations are covered up by official narratives to ‘harmonise’ the situation. With the shrinkage of this important space for public debate, and the deepening threats to those seeking to defend it, it has become even more difficult to hold the Chinese government accountable.

Conclusion

Can the recommendations of the Special Rapporteur help address this challenge? Unfortunately, key actions States could take rely on foundations such as an independent and impartial judiciary – something clearly absent in the Chinese justice system – and on detailed transparency reports – a hard-sell in China, where anything related to national security is considered, de facto or de jure, a State secret. Chinese businesses could change their practices; indeed, China joined by consensus UN resolutions on the issue of business and human rights. But in an environment where independent civil society has nearly disappeared, the stakeholders needed to engage Chinese companies domestically would be taking enormous risks just to get to the table.

In an ideal world, the Chinese government and Chinese internet companies would, in theory, have the capacity and the influence to create a sea-change in how free expression online is protected and promoted. But in reality, the fragility of the regime and the cooptation of its companies mean that this capacity and influence instead pose serious threats to freedom of expression online for internet users within China, and increasingly for those beyond China’s borders.

For more information, contact Sarah M Brooks at s.brooks[at]ishr.ch.

查看普遍定期审议报告中文版,请点击这里

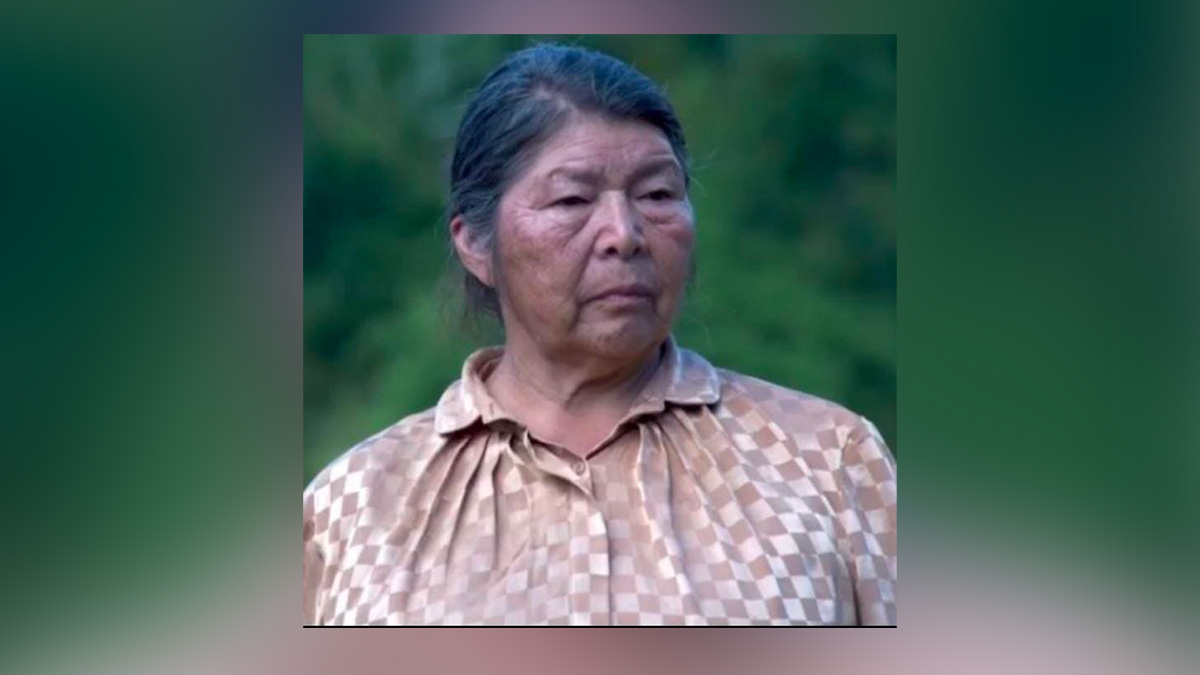

Photo credit: Flickr/Maina Kiai. License available here.