In China, like everywhere else, people want to live in dignity. They want to be able not only to meet their basic needs and care for their families, but also to express themselves freely and treat each other with fairness and respect. Unfortunately, the government perceives efforts to create a more inclusive, diverse, rights-respecting and just Chinese society as a threat to its power.

Cao Shunli, a brave woman human rights defender, attempted to speak truth to power by bringing the human rights situation in China to the attention of the United Nations. Her unwavering dedication led to her arbitrary detention by the Chinese authorities and ultimately to her tragic death after spending six months in custody, on 14 March 2014.

Cao’s story is not an isolated incident. It is emblematic of the broader crackdown on human rights defenders who dare to uphold the promise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in China. Many like her have been unjustly imprisoned, harassed, or forcibly disappeared. Many suffer from reprisals for attempting to cooperate with the United Nations, including by coming to Geneva like Cao tried to do. Yet, despite these adversities, human rights defenders in China continue to resiliently document, denounce, and mobilise against injustice.

In March 2024, ten years after Cao Shunli’s death, ISHR and partners pledged to carry forward her legacy by amplifying the voices of Chinese, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Hong Kong human rights defenders who continue to be targeted by the Chinese government. Our campaign achieved several milestones:

- On 14 March 2024, UN Special Procedures mandate holders renewed, for the third time, their public call on China to ‘fully and fairly investigate the circumstances that led to Cao Shunli’s death and hold those responsible to account’. The experts said that ‘failing to properly investigate a potentially unlawful death may amount to a violation of the right to life’ and that, ‘rather than using Cao Shunli’s death as a wake-up call and a moment to reform engagement with civil society, Chinese authorities have regrettably intensified their persecution of human rights defenders’. The experts further ‘noted that the participation of human rights defenders and civil society from China in UN human rights mechanisms and bodies has dropped to a record low’.

- That same day, nine European Human Rights Ambassadors released a joint statement honouring Cao Shunli’s legacy and calling on all States to stop engaging in acts of reprisals and to allow for safe and unhindered access to, and communication with, the UN.

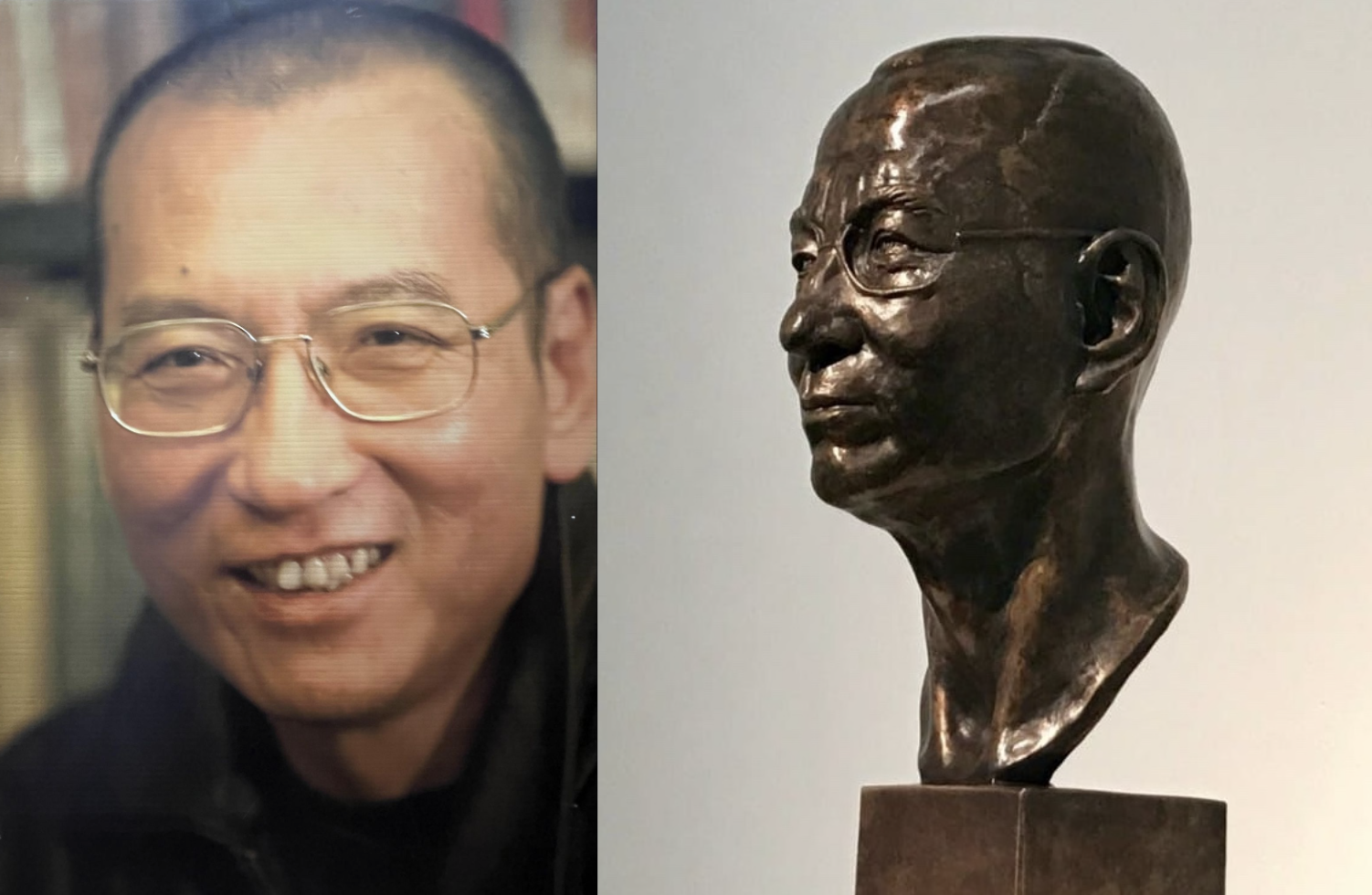

- Also on 14 March, 31 NGOs released a joint statement to echo the call for a probe into Cao Shunli’s death. ISHR and partners hold a day-long photo exhibition of persecuted human rights defenders, in particular women human rights defenders and paid tribute to Cao Shunli through a minute or silence and the unveiling of a bust of the activist on the emblematic Place des Nations. The event was reported in written and video by EFE.

- On 22 March 2024, an NGO joint statement was successfully delivered at the HRC paying tribute to Cao Shunli, during General Debate 5. Vain attempts by China, supported by Cuba, Venezuela, Russia and the DPRK, to interrupt the statement as they had done 10 years ago were countered by Belgium on behalf of EU Member States, the US, Canada and the UK, and by the HRC President’s decision to give the floor back to the speaker. These expressions of support have demonstrated to all Chinese human rights defenders (re)watching the session online that a range of international actors are committed to stand up for the right of civil society to speak at and engage freely with the HRC. This was reported in various continents by Reuters, AFP, EFE and Infobae, La Nación de Argentina, SwissInfo in Chinese, among others.

- On 25 April 2024, in a major campaign win, the City of Geneva announced their intention to host a public monument that would pay tribute to ‘the memory of human rights activists and the universal causes they embody’.

Cao’s powerful words, ‘But we must try!’, are a reminder for all of us, that even in the darkest of times, we must keep trying in our pursuit of justice. For only through our collective efforts can we hope to realise a world where human rights are upheld, cherished, and protected for all. This is Cao Shunli’s legacy.

Cao Shunli in 2013. ©Pablo M. DÍEZ (ABC Spanish Daily)