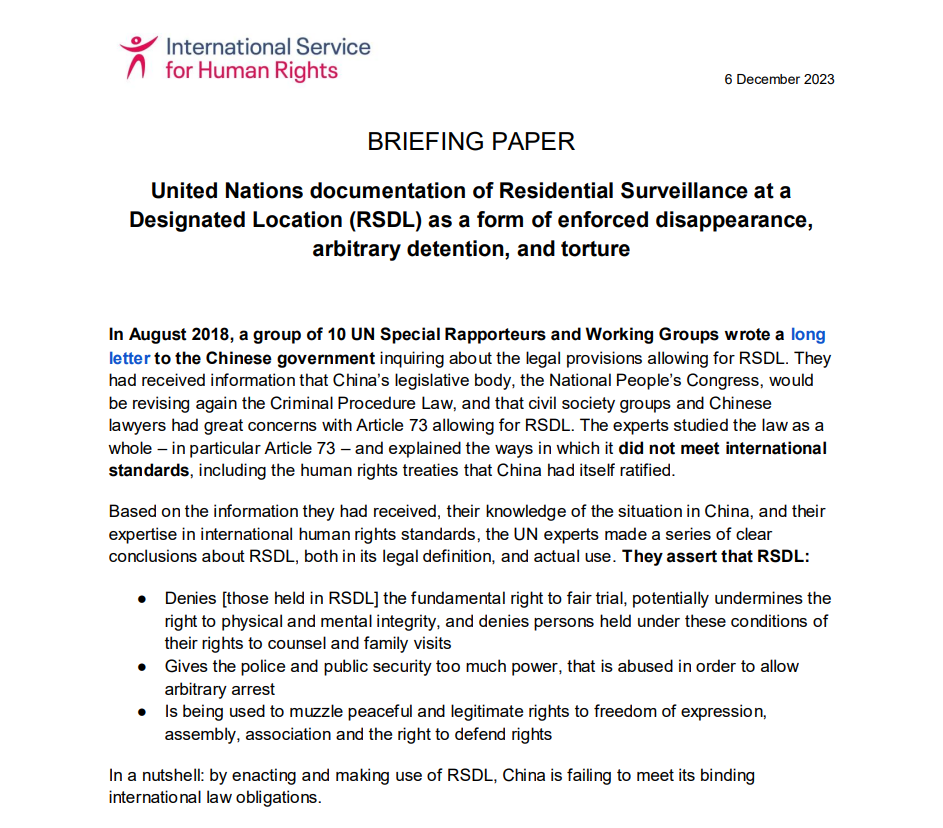

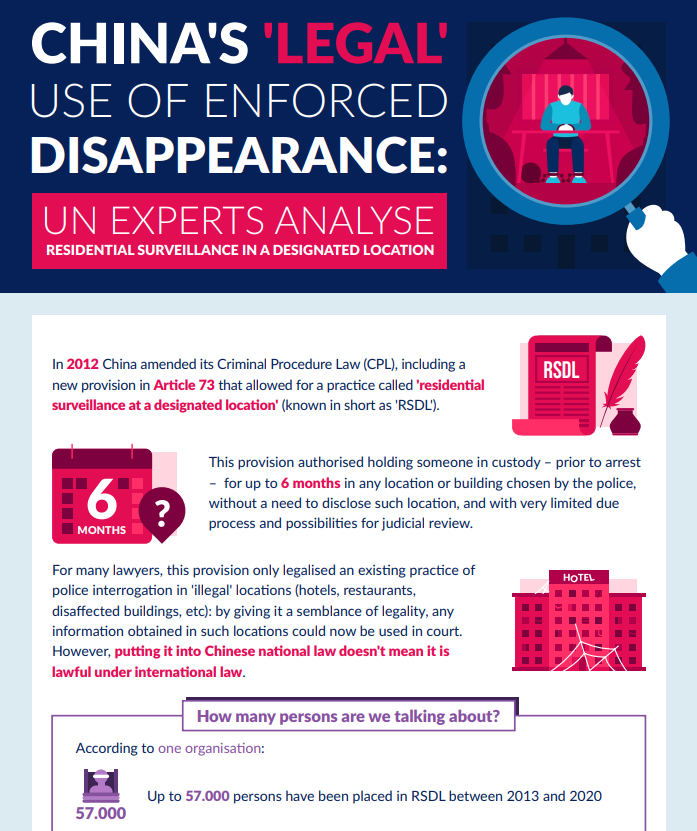

In August 2018, a group of 10 UN appointed human rights experts wrote a long letter to the Chinese government inquiring about the legal provisions allowing for RSDL. They had received information that China’s legislative body, the National People’s Congress, would be revising again the Criminal Procedure Law, and that civil society groups and Chinese lawyers had great concerns with Article 73 allowing for RSDL. The experts studied the law as a whole – in particular Article 73 – and explained the ways in which it did not meet international standards, including the human rights treaties that China had itself ratified.

Based on the information they had received, their knowledge of the situation in China, and their expertise in international human rights standards, the UN experts made a series of clear conclusions about RSDL, both in its legal definition, and actual use. They assert that RSDL:

- Denies [those held in RSDL] the fundamental right to fair trial, potentially undermines the right to physical and mental integrity, and denies persons held under these conditions of their rights to counsel and family visits

- Gives the police and public security too much power, that is abused in order to allow arbitrary arrest

- Is being used to muzzle peaceful and legitimate rights to freedom of expression, assembly, association and the right to defend rights

In a nutshell: by enacting and making use of RSDL, China is failing to meet its binding international law obligations.

In a March 2020 public statement, a group of experts including the UN’s Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) expressed their ‘alarm at the ongoing use of RSDL in China, despite having for many years reiterated the position that RSDL is not compatible with international human rights law’. They asserted that ‘as a form of enforced disappearance, RSDL allows authorities to circumvent ordinary processes provided for by the criminal law, and detain individuals in an undisclosed location for up to six months, without trial or access to a lawyer. This puts individuals at heightened risk of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.‘

In a September 2021 legal opinion on the cases of Zhang Zhan, Chen Mei, and Cai Wei, the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) ‘calls upon the Government to repeal the provisions governing RSDL’. It underscores the joint position adopted with other UN experts, that RSDL:

- ‘amounts to secret detention and is a form of enforced disappearance’

- ‘contravenes the right[s] of every person not to be arbitrarily deprived of his or her liberty, [to] challenge the lawfulness of detention before a court without delay, as well as the right of accused persons to defend themselves through legal counsel of their choosing’

- ‘may per se amount to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, or even torture, and additionally may expose [those held under RSDL] to an increased risk of further abuse, including acts of torture’

- is ‘used to restrict the exercise of the right[s] to freedom of expression, [of] peaceful assembly and of association by human rights defenders and their lawyers’

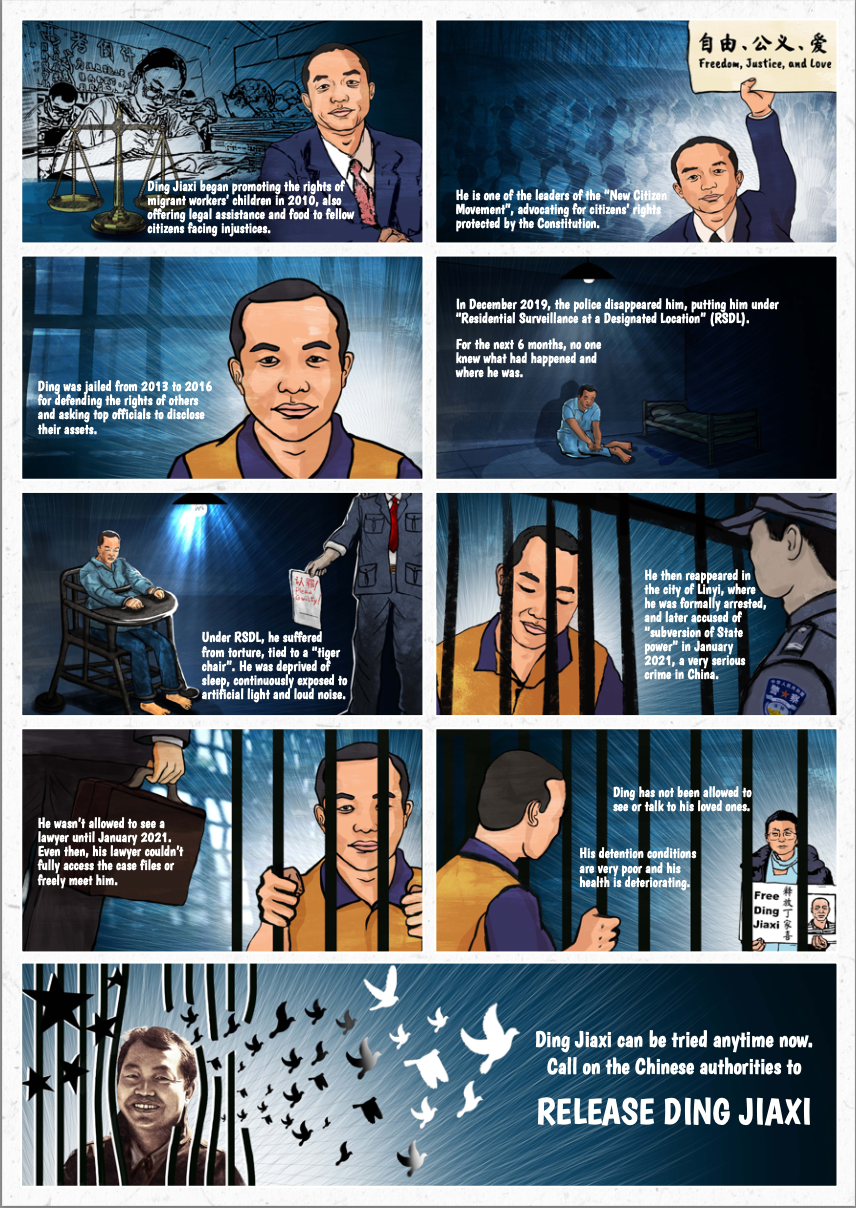

The WGAD recalled this position in its legal opinions on the cases of Yu Wensheng; Li Kai; Xu Zhiyong; Ding Jiaxi, Zhang Zhongshun and Dai Zhenya; and Wang Jianbing.

UN human rights experts have further reiterated their concerns over RSDL in letters to the Chinese government on the cases of Guo Feixiong and Tang Jitian (February 2022), Chang Weiping (September 2022), Huang Xueqin, Wang Jianbing and He Fangmei (December 2022), and Xu Zhiyong (May 2023).

In its 2023 annual report, the WGEID noted that the Chinese government has still – after more than ten years – failed to positively respond to their request to visit the country; at the same time, the overall number of outstanding cases of enforced disappearances taken on by the Working Group in the past six years increased by 147%, from 68 to 168.

Following her official visit to China in April 2022, the then UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet reiterated that UN human rights bodies have categorised RSDL as a form of arbitrary detention and called for its repeal.