A newly-released report, China and the UN Economic and Social Council, consolidates, for the first time, research by ISHR, other civil society organisations and traditional media. It provides an overview of the way in which China has extended its representation throughout the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and its subsidiary bodies and processes, enabling the Chinese government to significantly influence the UN’s development priorities and cooperation with civil society.

The primary author, ISHR programme director Sarah M Brooks, reflects that ‘the Chinese desire for leadership and the competition for directors’ positions is not news.’

‘What this briefing note does is contextualise the Chinese government’s pursuit of UN agency leadership – to demonstrate how this is complementary to efforts to embed its other national priorities.’

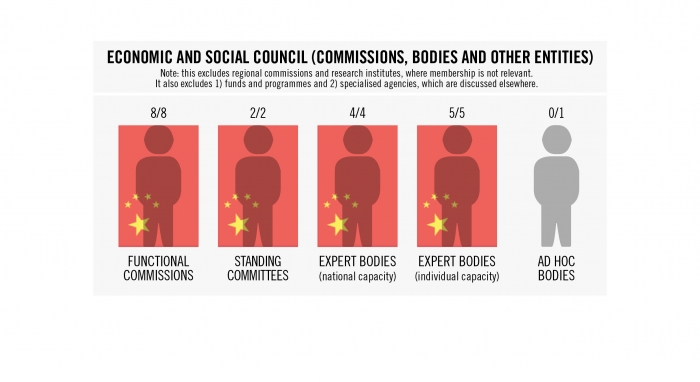

Chinese government representatives, serving in their official or nominally-personal capacities, and government delegations themselves have been appointed or are active across ECOSOC bodies and agencies at the highest levels, the briefing shows. The near-universal coverage ensures that standard-setting and grant-making within these UN bodies are highly aligned with Chinese flagship issues, such as the right to development, ‘counter-terrorism’ and above all, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Human Rights Watch’s China Director Sophie Richardson has followed this growing alignment with deep concern. Speaking at a briefing to launch the report, she noted of the UN’s extensive adoption of BRI language:

‘The UN has no business giving political legitimacy, an imprimateur of approval, where it’s not only not necessarily deserved, but also where there has been an absence of scrutiny.’

The research also looks into the ways in which China seeks to act, in concert with other governments, as a gatekeeper to UN access for non-governmental organisations – even those whose work has nothing to do with China’s domestic situation – while at the same time facilitating access for a growing number of organisations aligned with Chinese government and party views.

Academic and expert in the workings of the NGO Committee, Dr Rana Siu Inboden, made similar observations about China’s active role in holding back civil society participation:

‘Over the period I researched, China alone blocked or delayed 25% of the applications from NGOs. Not only did China look out for its own equities, but it did the bidding of authoritarian allies. This was especially true in the case of the DPRK, where it blocked nearly every NGO that works on human rights in North Korea’.

At the same time, some civil society is welcome, notes Brooks. Government-organised NGOs, or ‘GONGOs’, represent an estimated half – at least – of all China-based organisations who have a standing ‘stamp of approval’ to participate in UN meetings. The intentional and highly effective exclusion of Taiwanese officials, organisations, and individuals from any UN space further exacerbates the unequal representation. And finally, the use of ad hominem and procedural attacks on certain activists, namely those from ethnic minority diaspora communities, send a chilling message.

‘The brazenness with which Chinese officials call for the exclusion of critical voices – and the not-uncommon response of the UN system to acquiesce – point to a clear trend of intimidation and reprisal to shut down dissent in UN spaces,’ says Brooks.

Finally, the briefing note points to some examples of Chinese government discourse that have been the centre of UN negotiations. On the one hand, the Chinese government has seen success in ensuring that its hallmark turns of phrase become ‘agreed language’, or part of the UN lexicon. On the other, the persistent unwillingness to specify precisely what is meant by such language has driven many delegations to push back on the inclusion of the language, which often has its origins in Chinese Communist Party rhetoric.

The report authors highlight recommendations for steps that every government can take to strengthen the independence and transparency of the ECOSOC system and to ensure that it is ‘fit for purpose’ in pursuing the UN’s objectives of peace and security, sustainable development, and human rights.

Finally, the briefing note also leads to other questions and areas for future inquiry. For example:

- While extensive attention has been paid to the highest levels of UN leadership, are UN officials in middle-management or more junior levels also impacted by the potential conflict of interest between upholding the independence of the UN civil service and toeing the line of home country ‘interests’?

- Is the model of the UN Peace and Development Trust Fund unique, or standard practice for UN Member State-donated funds? What safeguards are in place to ensure responsible stewardship of these monies, and alignment with principles of universality?

- What are the practical implication of the extensive investment by Chinese-donated funds to the UN’s counterterrorism directorate?

- How can GONGOs be better tracked and identified, and what steps does the ECOSOC secretariat undertake to ensure that objective criteria inform, to the fullest extent possible, threshold considerations of ECOSOC accreditation requests?

Dr Siu Inboden is also the author of China and the International Human Rights Regime.

Download as PDF