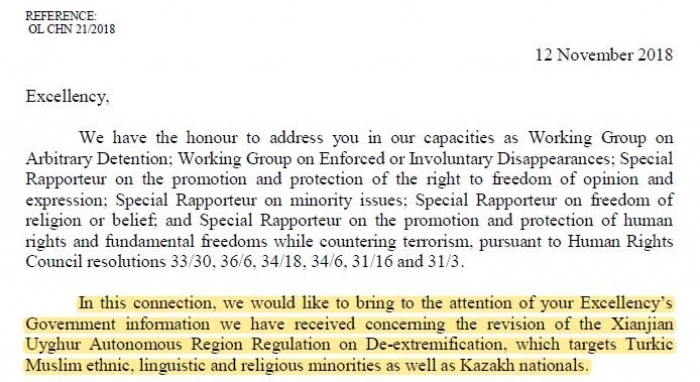

Raising concerns about massive repression and the government’s stated aim of homogenising Chinese society, UN experts weighed in on the tug-of-war between China and Western countries about how to characterise the situation in Xinjiang. Their analysis of provincial-level regulations on ‘de-extremification’, which were amended on 8 October to justify the use of re-education facilities, clearly demonstrates a range of areas where the regulations are incompatible with China’s international human rights obligations.

The experts clearly confront a narrative promoted by the Chinese authorities that these measures are needed to, as stated in the UPR as well, ‘prevent terrorism’, saying:

We are aware of the many security challenges that China faces and of the duty of the State to ensure the safety and security of its people, including through preventive approaches. However, we are gravely concerned that the Regulation’s measures to address this objective are neither necessary nor proportionate.

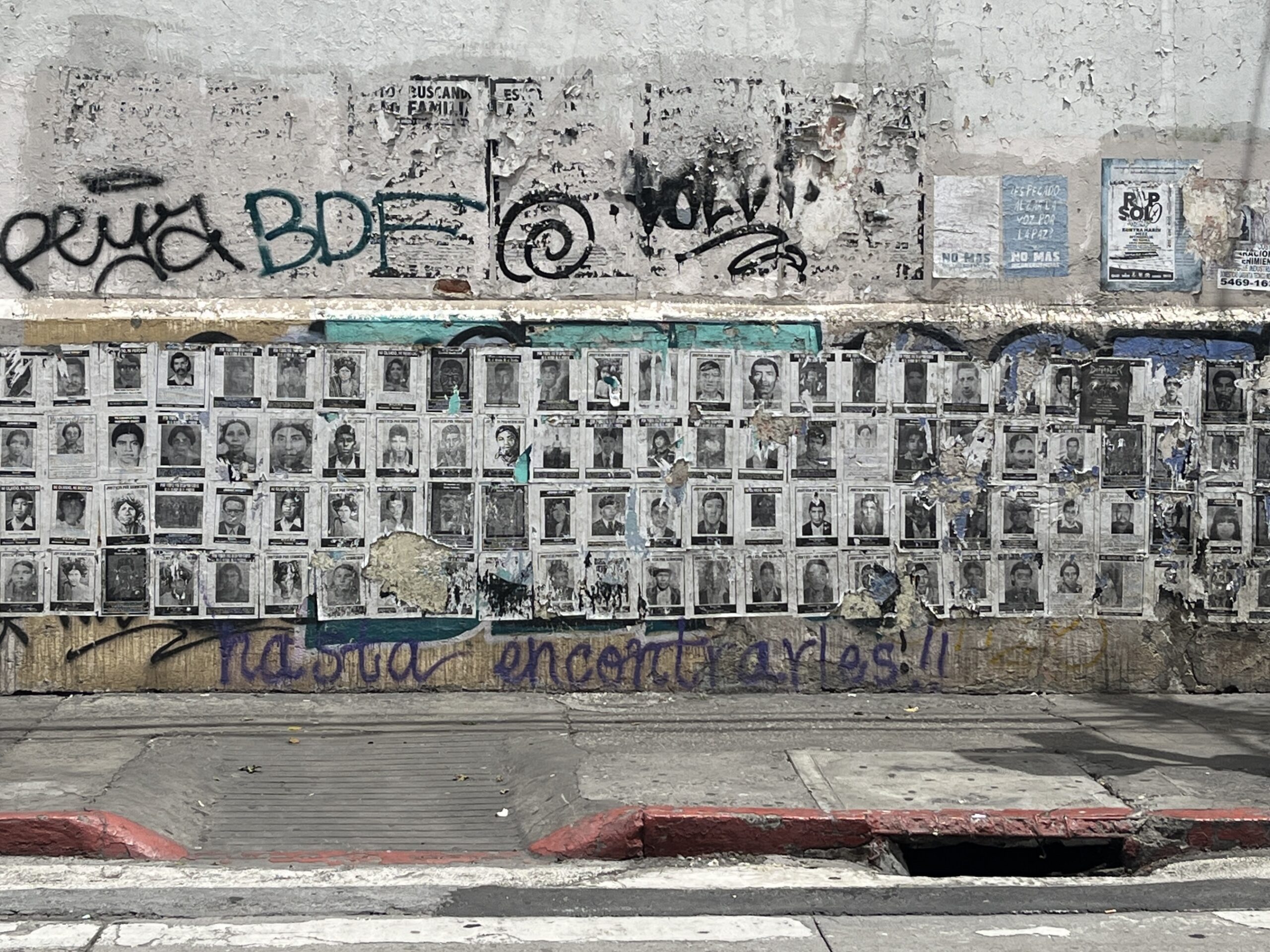

The specific measures under review are the involuntary and extra-legal detention of individuals in re-education centres, which the Chinese government has sought to cast as ‘vocational training centres’. Other, less stark but no less serious, measures implemented in the region include restrictions on religious and cultural expression, banning Muslim names and Islamic texts, subjecting Uyghurs to extreme levels of physical and digital surveillance, and blocking or discouraging sharing of information, including among family members.

The experts add that they are ‘particularly disturbed by the recurrent referral to extremism, not only in Xinjiang but across the country, to justify numerous measures limiting freedom of expression and belief, and inhibiting political dissent’ and that the revision of the Regulation on De-extremification occurs in this context of ‘increasing pressure and repression of fundamental rights’ throughout China.

They conclude with a call for the repeal of the regulation and reiterate their desire to visit the country. This is timely and important, in light of their view that ‘despite China’s legal obligations and commitments, multiple laws, decrees and policies, in particular those concerning national security and terrorism, deeply erode the foundations for the viable social, economic and political development of the society’.

Sarah M. Brooks, ISHR’s Asia advocate, has been following closely the efforts by the UN to call for transparency and accountability for China’s treatment of minorities.

‘In the last four months or so, we’ve seen an almost unprecedented number of UN inquiries about China’s treatment of its ethnic minorities, including Uyghurs and Tibetans. The UN Special Procedures should be seen as the canary in the coalmine, alerting the global community to extreme measures the Chinese government will take to maintain political control and suppress any form of dissent within its borders.’

‘However, we should also take note,’ Brooks adds, ‘that these policies don’t stop at borders. They have a serious chilling effect on families in the region and on activists in exile. Governments – European and otherwise – have yet to show sufficient political will to meaningfully address this threat. It’s time they stepped up and honoured their commitment to protect human rights and their defenders.’

The full English text of the letter is available here, and we have prepared a short summary in Chinese.

Update: Between 13 and 14 November, the letter from the UN experts to China appeared to have been removed from the website of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. It was returned to the database and publicly accessible on 15 November. ISHR and other NGOs have previously raised concerns about the removal or censorship of information about China from UN websites and publications; we remain concerned about the transparency of this practice, together with the apprehension of pressure or influence from China, and welcome dialogue with the Office in this regard.