The results are in, and Hong Kong falls short.

Following a fraught series of exchanges earlier this month at the review of Hong Kong by the UN Human Rights Committee, the UN has released its official set of views and recommendations. While recognising some progress in the area of anti-discrimination, gender equality and migrants’ rights, the experts assess that the National Security Law for Hong Kong (NSL) has significant ‘shortcomings’, and its application has ‘unduly restricted a wide range of Covenant rights’. This includes:

- ‘Certain provisions of the National Security Law [that] substantially undermine the independence of judiciary and restrict the rights to access to justice and to fair trial’

- The ‘ineffectiveness’ of the complaint mechanisms for persons deprived of their liberty, as well as those alleging police violence and those seeking to challenge enforcement of the NSL

- The ‘adverse effect of the overly broad interpretation and arbitrary application of the National Security Law and sedition legislation, and its impact on the exercise of freedom of expression’

Sarah Brooks, ISHR Programme Director, puts it bluntly: ‘The experts’ observations show without a shadow of doubt that the rule of law in Hong Kong is in peril’.

The Human Rights Committee‘s concluding observations for Hong Kong highlight major issues that the government should address in order to comply with its obligations. Some of these are flagged as priority. This means that from now, for the next three years, there will be particular scrutiny of these concerns, and extended engagement by Committee members to ensure they receive information from all stakeholders. Those recommendations are:

- That Hong Kong should take ‘concrete steps’ to repeal the NSL, and in the interim, cease applying the law (para 14);

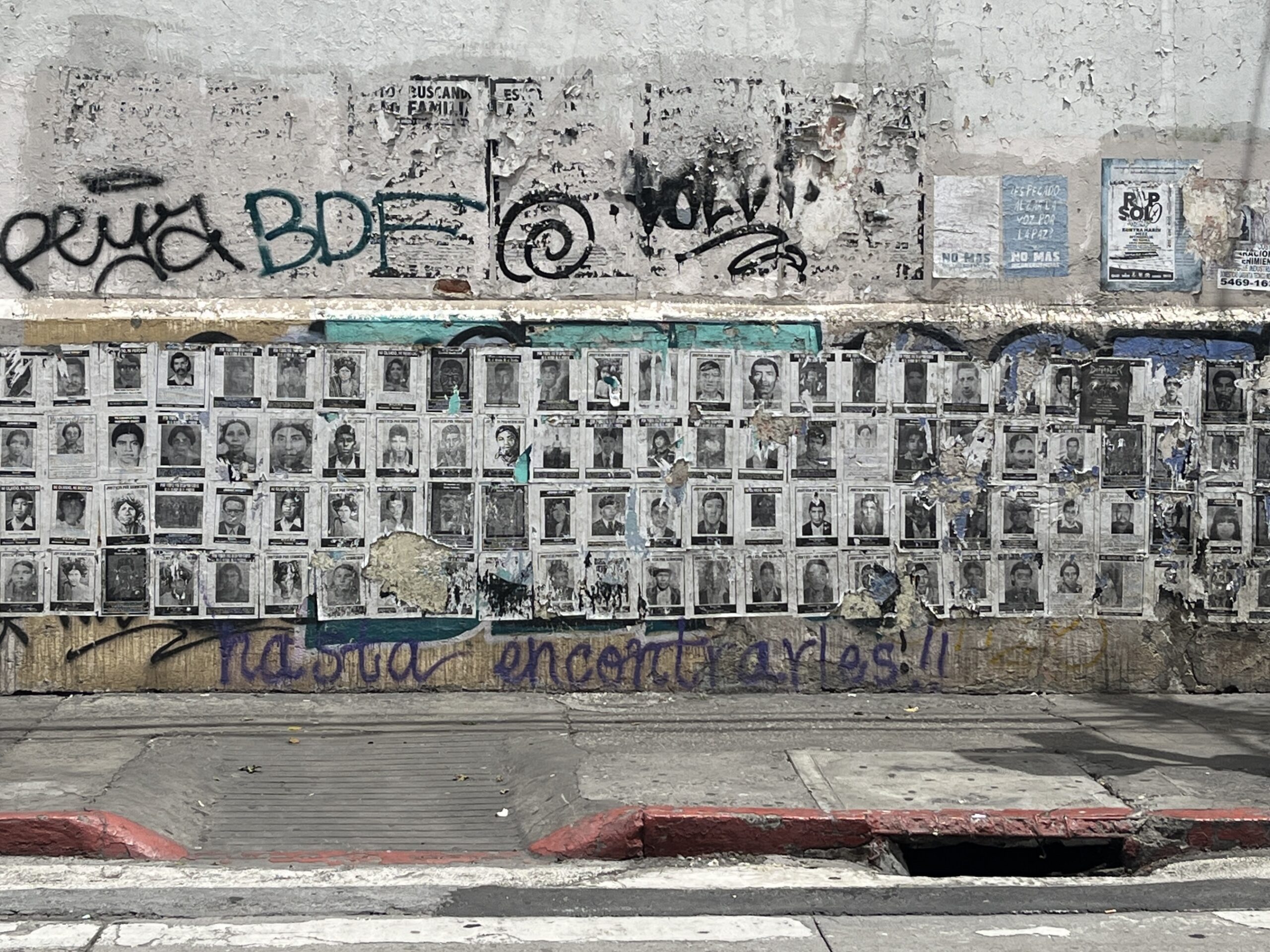

- That Hong Kong should cease targeting human rights defenders, journalists, and others with the NSL and sedition laws, and release and provide compensation to all those detained for exercising freedom of expression (para 42);

- That Hong Kong should stop any actions, and remove any restrictions, aimed at limiting civil society organisations and trade unions from doing their work (para 50);

- and that Hong Kong should ensure that the NSL and other laws will not be used as a form of reprisal against civil society for engaging with the Committee, other UN human rights mechanisms, and international civil society (para 50).

‘Just as with the review, the follow-up process is only as good as the ability for civil society to participate,’ says Brooks. ‘This is why it is absolutely crucial that the concern about reprisals be addressed in particular. Communicating with the UN is a central part of the work to defend human rights, and criminalising it is unacceptable’.

ISHR further denounces the ongoing crackdown on peaceful dissent and free speech in the city. Brooks adds, ‘Whether you are a trade union, a student group, a local politician or a community worker, the overly-broad nature of national security “crimes” creates a chilling effect on legitimate, important work of advocacy to keep Hong Kong democratic and rights-respecting’.

Upcoming court hearings and anticipated draft legislation provide an opportunity to assess whether and how Hong Kong’s executive and judiciary will act in good faith to improve their rights record.